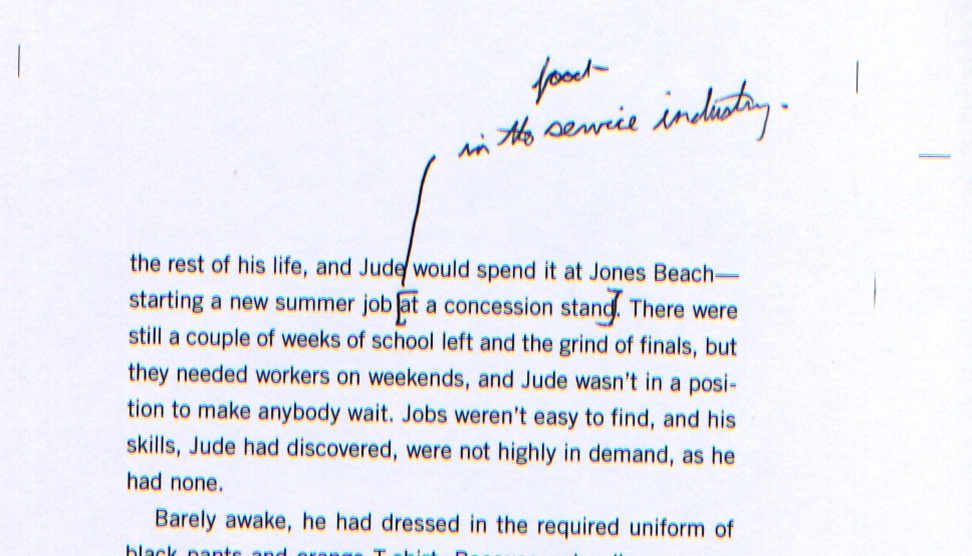

Last month I handed in the manuscript for the first book in a new series — my first since Jigsaw Jones. Though Jigsaw is still around, with many titles still available, I haven’t consistently written new books in that series for the past six years.

In the intervening time, I’ve published hardcover books, a first for me, in picture book format (Mighty Casey, A Pirate’s Guide for First Grade) and for older readers (Six Innings, Along Came Spider, Justin Fisher Declares War, Bystander, and Before You Go).

I haven’t written specifically for what was once my core readership, the grades 2-4 crowd. I needed to step away, explore different things. But now I’m back, writing 80-page chapter books for exactly that age group. And I have to tell you, I’m absolutely in my comfort zone with this new, evolving series — my “Twilight Zone” for younger readers.

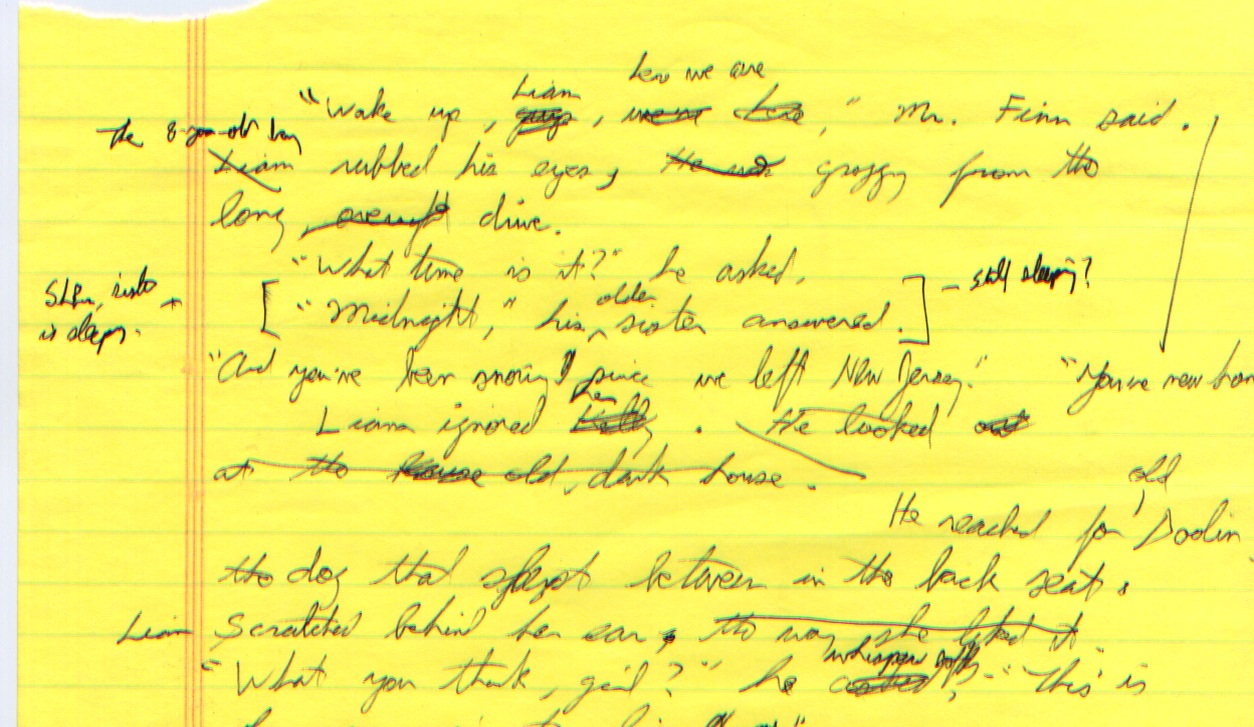

Here’s a sample page 1 from my first draft, scribbled out on a yellow legal pad (as if my usual practice):

Kind of messy, right? Not sure you can read this. Lots of interesting changes/revisions/improvements on the fly. I gave the sister an early line of dialogue, then to the side, later, asked myself: “still sleeping?” Brought “Our new home” up into the first paragraph, deleted words and phrases, etc.

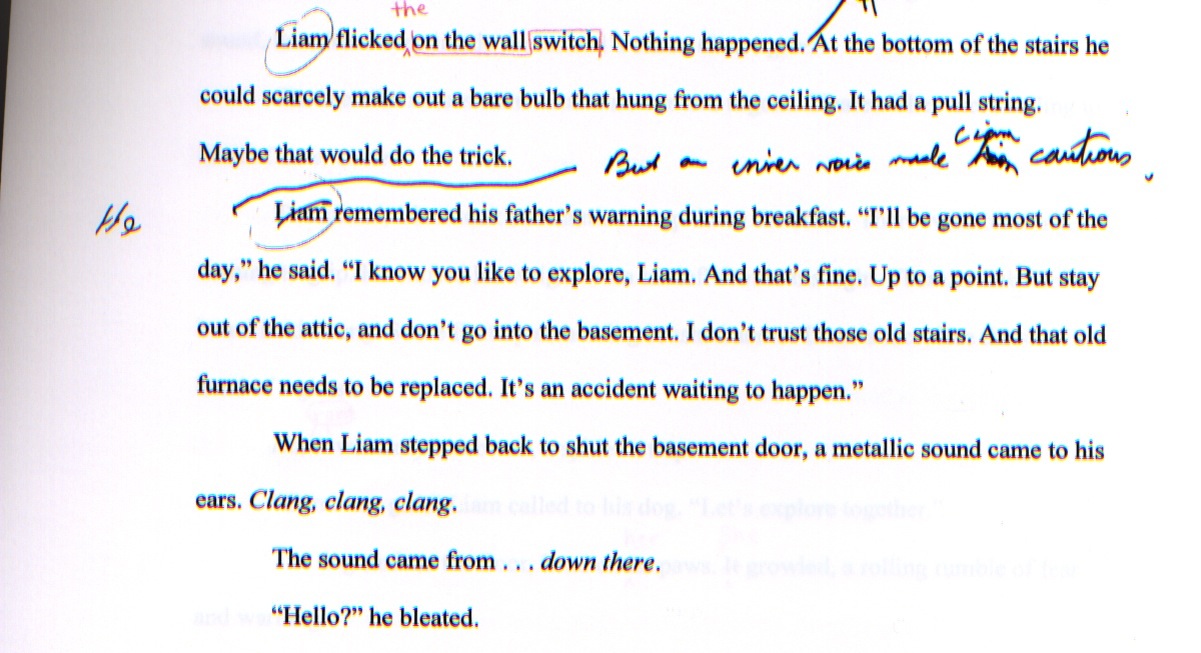

Last week I received the copyedit in the mail, which I reviewed over the phone with my editor, Liz. So now that same section looks like this:

The ring, I learned as I wrote, figures large in the story. There is a power to it. So during revision I made sure to get it into that opening scene, underscoring Kelly’s relationship to it, giving it, in other words, its moment.

I was grateful to receive positive feedback from my publisher, since the first book in a new series can be tricky. You make many decisions that you’ll have to live with for the length of the series. Jean Feiwel sent me a note, “I love love love this book.” That was good day. I was not asked to make any big changes, just light revisions. In another month or so I’ve receive the galleys, with the corrected type set in a carefully-selected font, exactly as it will appear in final book form, and with it the opportunity for another round of tweaks, improvements. The artwork will come in within the next two weeks — and there will be a lot of it. That’s exciting. I can’t wait to see what the (super-talented, surprise) illustrator does with the story. All the while, I’m writing the second book of the series, which is due in another month.

The series, tentatively titled “Shivers,” will launch in the summer of 2013.

EDIT: Now called “SCARY TALES.”

Starting a new series presents many challenges, the thrill of creating something brand new. Hopefully this will be the beginning of something great. That’s always my dream going into a job, “Maybe this one will be great.” I don’t think I’ve gotten there yet, but I keep hoping.

We are not interested in creating a formulaic set of stories, stamped out by a factory. We want each book to stand alone, featuring different characters and different settings. Again, in this sense, I am inspired by Stephen King and “The Twilight Zone” (and yes, I own the complete series on DVD), which rather than one type of story, featured a comprehensive variety of sub-genre, including science fiction, horror, social satire, fantasy, ghost stories and countless variations. My hope is that across a number of books we’ll be able to accomplish something similar in terms of scope and content, while still maintaining a signature fingerprint. When a reader opens a “Shivers” book, he’ll know that he’s about to get strapped into the roller coaster, taken for a wild ride, and returned back safely again — hopefully screaming, “Again, again, again!”

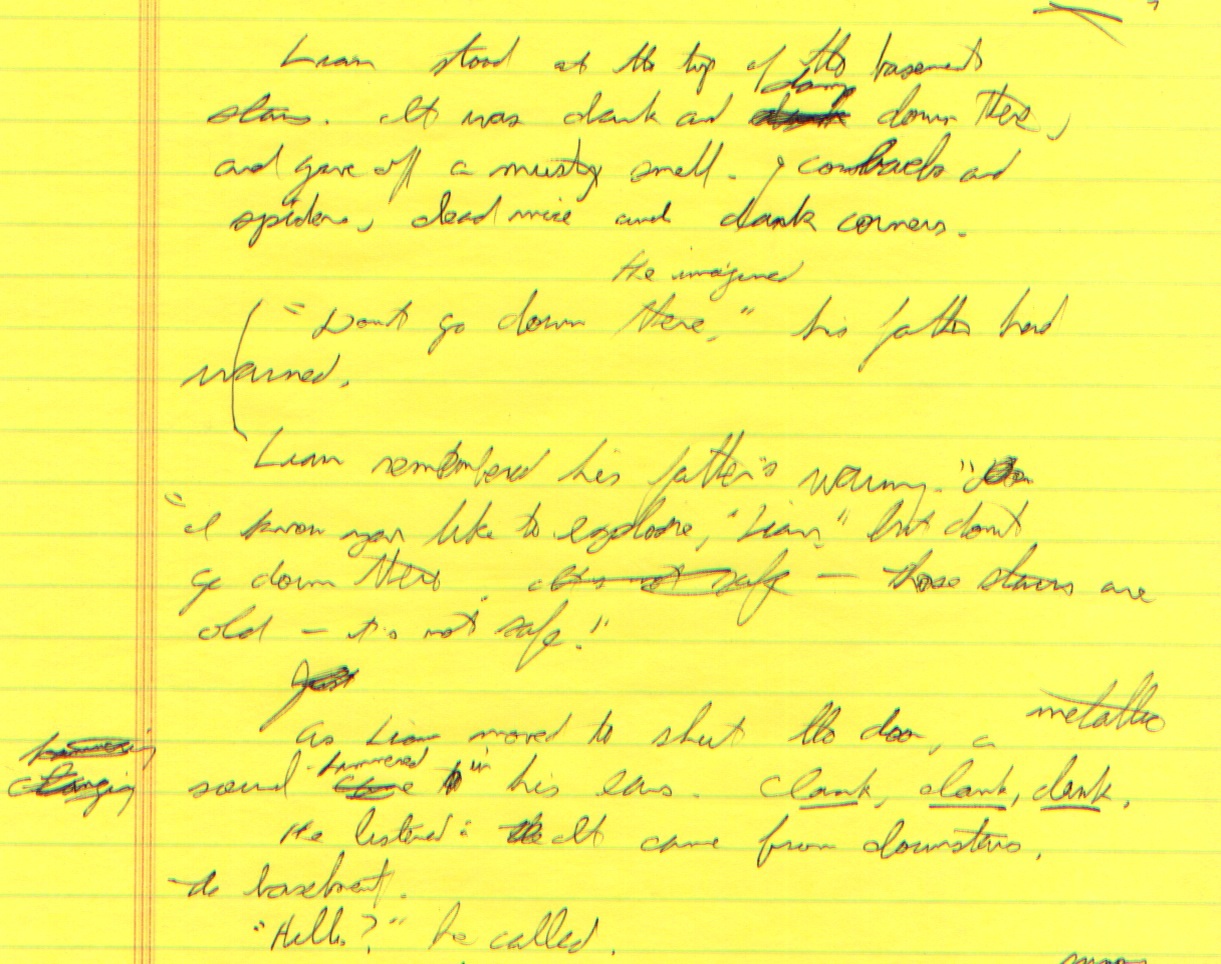

For fans of process, here’s another example of how the story moved from first draft to copyedit:

The copyedited version, which arrives after many revisions by me at home before it goes to the publisher, represents the first edited response from my publisher. Again, this sample shows a light touch by the folks at Feiwel & Friends, thank goodness. Note the circles around “Liam.” We commonly refer to this as an echo. Sometimes when we use a word too many times over a few sentences, or when, in this case, the paragraphs open in the same way. Doesn’t mean it must be changed, just that it should be looked at, considered, before it is changed or not. Alert readers will also note that I changed “‘Hello,’ he called” to “‘Hello,’ he bleated.”

A little lamb, lost in the wilderness.

Have a great Memorial Weekend, everybody. And please remember why we celebrate it. Be grateful to the uniformed men and women who have served our country over the years.