I have to share this brilliant piece from The New York Times Sunday Review, March 18, 2012, written by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Jhumpa Lahiri. I powerfully identified with it.

In it, she expresses her love of sentences. Everything about this piece confirms, echoes, and expands upon my own feelings as a writer and a reader. Though we’re told that Lahiri’s piece is part of a series about “the art and craft of writing,” it is just as much about reading. Perhaps more so. Teachers, librarians, editors, readers, please check out it.

Art by Jeffrey Fisher.

Here’s the opening . . .

In college, I used to underline sentences that struck me, that made me look up from the page. They were not necessarily the same sentences the professors pointed out, which would turn up for further explication on an exam. I noted them for their clarity, their rhythm, their beauty and their enchantment. For surely it is a magical thing for a handful of words, artfully arranged, to stop time. To conjure a place, a person, a situation, in all its specificity and dimensions. To affect us and alter us, as profoundly as real people and things do.

I remember reading a sentence by Joyce, in the short story “Araby.” It appears toward the beginning. “The cold air stung us and we played till our bodies glowed.” I have never forgotten it. This seems to me as perfect as a sentence can be.

As I’ve said before on this blog, that’s how I read — pen in hand, underlining sentences, making marks, asterisks and exclamation points, my beloved marginalia. But the thought that really had me nodding in agreement was how the best sentences made me stop reading. I looked up from the page, thinking, feeling, dreaming. It’s counter-intuitive. We want readers to keep turning the pages, right? To devour the book, consume it. Well, maybe not. Maybe we want them to slow down, or stop altogether.

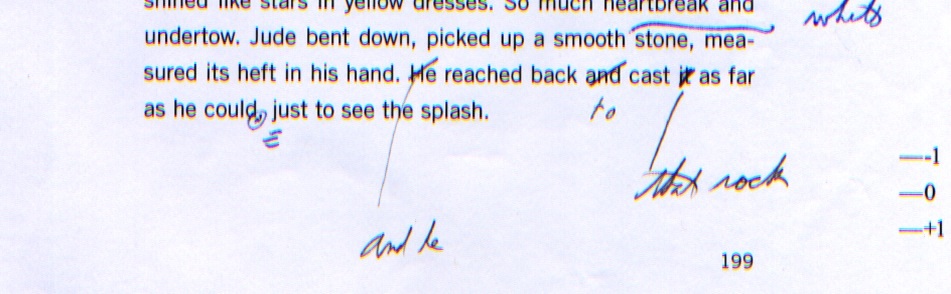

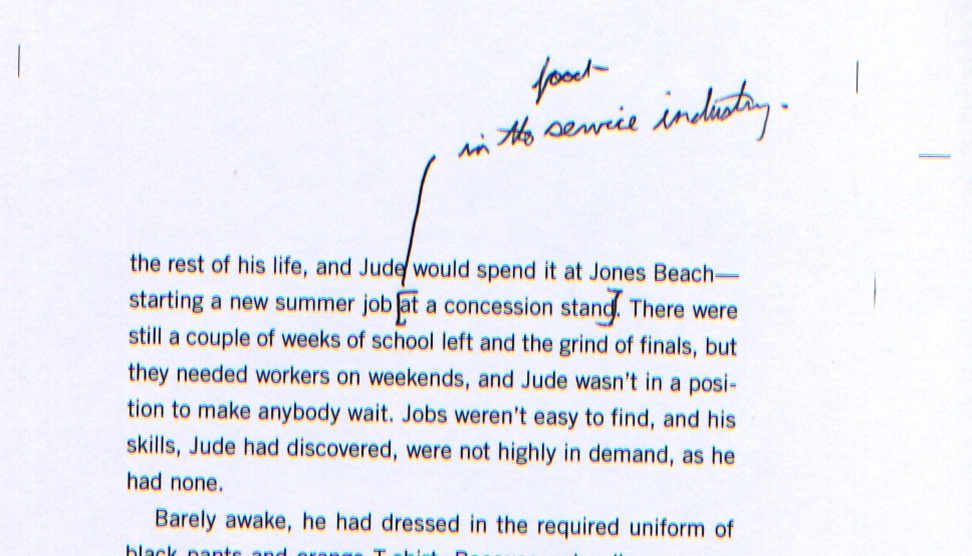

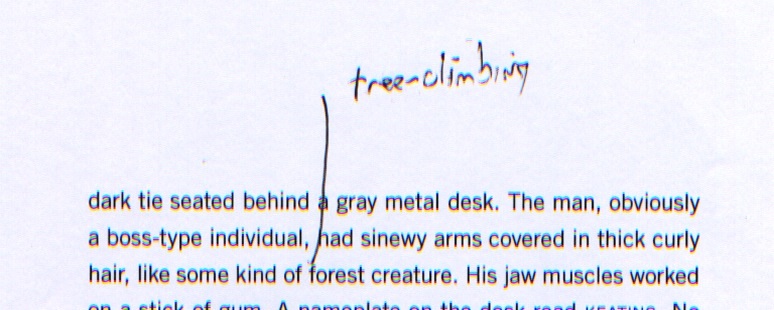

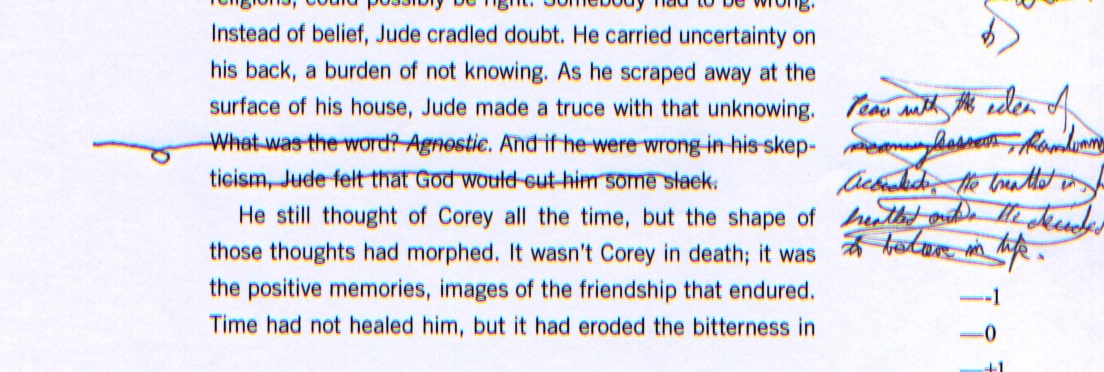

From my copy of Let the Great World Spin, by Colum McCann.

That’s why, I think, that I’m so often uncomfortable when I encounter the counters and the tickers, the well-meaning folks who inform us how they read exactly 214 books this year and so on. I don’t mean to insult anyone, but I’m so tired of the idea of quantity.

Pause and reflection, that’s reading too.

Of course, there are different kinds of reading. Librarians, for example, tend to read with an ultimate user in mind. So he burns through a Percy Jackson book (doesn’t that kill you when folks use that language, burning through a book), wanting to be familiar with it, but mostly thinking, “I can’t wait to give this book to about twelve boys I know.” That’s an altogether different reading experience — and probably a topic for another day.

Speaking of sentences, here’s a sturdy one:

The best sentences orient us, like stars in the sky, like landmarks on a trail.

And in the next paragraph:

They remain the test, whether or not to read something. The most compelling narrative, expressed in sentences with which I have no chemical reaction, or an adverse one, leaves me cold.

This is exactly why I could not continue reading Twilight, for example. For me, there was no spark in the sentences, no electric connection between writer and reader. I couldn’t even get past them to story.

Sentences are the bricks as well as the mortar, the motor as well as the fuel. They are the cells, the individual stitches. Their nature is at once solitary and social. Sentences establish tone, and set the pace. One in front of the other marks the way.

Another sentence to underline:

My work accrues sentence by sentence.

So true, could it be any other way? Bird by bird, sentence by sentence, brick by brick.

I hear sentences as I’m staring out the window, or chopping vegetables, or waiting on a subway platform alone. They are pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, handed to me in no particular order, with no discernible logic. I only sense that they are part of the thing.

I talk to students about this in a different way, more about ideas than sentences. Those times when you are thinking that you are not thinking. That’s often when the ideas come, when the sentences, unbidden, line up inside your skull. I know a book is going well when sentences come to me in the shower.

Last thought — and please, go to the original piece, read it in full — I also connected with Ms. Lahiri’s concept of revision:

All the revision I do — and this process begins immediately, accompanying the gestation — occurs on a sentence level. It is by fussing with sentences that a character becomes clear to me, that a plot unfolds. To work on them so compulsively, perhaps prematurely, is to see the trees before the forest. And yet I am incapable of conceiving the forest any other way.

Students are taught the writing process in school, the five steps, brainstorming and so on, that it’s easy to imagine each as isolated, distinct from the other. In fact, many experts advise writers to “just write” in the beginning, get the words on the page, don’t worry about mistakes. And while I understand that point of view, that’s never been how I do it. Revision begins instantaneously, inextricably linked to the writing impulse. In this age of trumpeting daily word counts on status updates — “1,687 words today!” — it’s nice to read that maybe I haven’t been doing it completely wrong after all.

When something is in proofs I sit in solitary confinement with them. Each is confronted, inspected, turned inside out. Each is sentenced, literally, to be part of the text, or not. Such close scrutiny can lead to blindness. At times — and these times terrify — they cease to make sense. When a book is finally out of my hands I feel bereft. It is the absence of all those sentences that had circulated through me for a period of my life. A complex root system, extracted.

I have just been through this with my upcoming book, Before You Go (Macmillan, July 2012).

And though all my favorite writers are great sentence-makers, with this novel I came closest to that ideal. This book has my best sentences. Each confronted, inspected, turned inside out. Yes, the sentences are vehicles for ideas, feelings; they carry story on their shoulders. But story itself consists solely of sentences, sounds, rhythms, meanings. And now that my book is at the printer — hey, before you go! — too late, too late! — I too feel a bit bereft.

The only way out of that hole is to write a new story. Sentence by sentence.

Go here to learn more about Jhumpa Lahiri.