Lewis, I was just so impressed with your new book, BRIDGE OF TIME (Macmillan, May 2012). Congratulations. When I was reading the Advance Reader’s Copy, I wished I could talk to you about it, ask questions, dig a little deeper. Then I realized: Hey, I operate my own fully-licensed blog right here in America. I’m kind of a big deal. So I figured I’d invite you over and we’d talk it out. (Besides, Vonnegut is not answering my emails.)

That’s odd. Kurt and I were just talking the other day. So it goes.

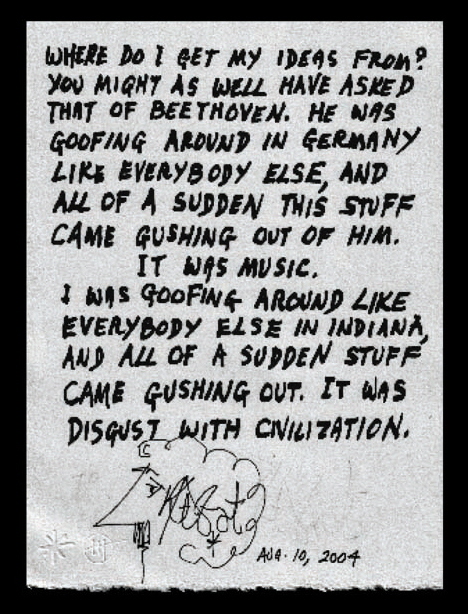

I mentioned Vonnegut almost randomly, since as a matter of policy I drop Vonnegut’s name as often as possible, but thinking of it now, old Kurt dabbled quite a bit in time travel himself. Billy Pilgrim — of Ilium, New York –- tumbling from past to present to future. And it seemed totally natural, not science fiction –- that yes, life is like that, we’re constantly traveling through time in our heads.

“Unstuck in time” is the phrase Twain used here to describe Time Travel, and I lifted unapologetically from SLAUGHTER-HOUSE FIVE. Vonnegut is too important, I agree, to overlook, especially today. But it also seems to me that Vonnegut is a direct heir to Twain. In the book, Twain makes a passing reference to his friend Kurt, whom he met while unstuck in time, and it was Kurt who coined the phrase.

That’s a wonderful detail, Lewis. In my upcoming Young Adult novel, BEFORE YOU GO, one of the central characters just finished reading BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS. There’s really no big reason for it, other than to tell you something about that character’s likes and interests. Frankly, I loved the idea of four teenage boys in a car, talking — however briefly — about Kurt Vonnegut — and it leading to a minor argument. That’s Kurt, always stirring things up. We do what we can to pay homage to our heroes.

Writers, for the most part, become writers because they started as readers. We’re nothing without those who came before us. We owe them all the props. Especially Vonnegut for me. When I was sixteen, I read SLAUGHTER-HOUSE FIVE, and my world was never the same.

This is the third book in what I like to think of as your “Dead Author” trilogy, following STEINBECK’S GHOST and THE HAUNTING OF CHARLES DICKENS. In this story, we meet Sam Clemens, who later goes on to fame and fortune under the pen name, Bret Easton Ellis.

I prefer to call these “literary mysteries.” And no, not Bret Easton Ellis. Some of Twain’s writings are actually in the more advanced past tense.

Oh, wait, you’re right. My bad. The girl who usually comes in to shuffle my note cards has been out sick. Hold on, give me sec.

Color coding, my friend, that’s what it’s all about. Works for socks and other underthings as well.

Ah-ha, Twain! That’s it. Um, okay, each book is thematically linked, but not at all formulaic. Reading one tells you nothing of the others.

I really didn’t want to write the same book with plug-in characters. And I tried to offer different aspects in each book. Steinbeck has a male protagonist, Dickens a female, and with Twain, one of each. I also tried to look at different aspects of a writer’s life. In Steinbeck, the writer himself is dead and remains as a spirit, in the form of his books. With Dickens, I was looking at The Great Man as a living author, but a fully successful one. With Twain I focused on that crucial summer when Twain made the jump from journalist to fiction writer, when Clemens really became Twain.

To me, that decision was central to the book’s success. We meet Sam Clemens, struggling writer, not “Mark Twain,” established literary lion. Clemens, like the main characters, Lee and Joan, is still unformed. We can relate to him. All three main characters are poised on the verge of becoming. The future awaits them, exciting and terrifying. I love that about your story, and really it’s what I love about children’s literature in general. There’s this beautiful sense of self-realization, of youth unfurling, of learning how to be. Your book celebrates the cusp of life.

This is one of the reasons I love to write for middle grade readers, because that’s what their whole lives are about, bidding farewell to childhood and entering into the murkiness of the grown-up world, with just enough awareness to be both brilliant and naive in their choices. I remember that so much from my own junior high life, how much I tried on different costumes and personae, trying to see what fit, and all the while watching the adults around me and trying to figure out how they became who they were now.’

I’m fascinated by middle schoolers, it’s such an age of transition, false starts and new beginnings. Filled with self-doubt and uncertainty. Who am I, where do I belong? Everything is up for grabs, which is tremendously exciting, because it’s also a time of great possibility. As you know, I have a 7th grader in my own house, and as maddening as he’s become –- and I confess to sometimes wanting to strangle him, his eye-rolling impatience — I often feel great sympathy for my son: the hormones, the emotions, the explosion of brain cells in the frontal cortex. It’s a wild ride. The saddest aspect about middle school life is their desperate desire to fit in, their longing to belong, and that often manifests itself in dull conformity. Everyone wearing the same clothes, worried about what everybody else thinks.

That’s the great conflict, isn’t it? Wanting to fit in, yet dreaming of being your own self. My daughter is in 8th grade — more eye-rolling than 7th — and I see her working hard at both. I do think this is one thing that the best middle grade novels — heck, any of the best novels — can do, give the reader permission and courage to find themselves in that grand sea of confusions.

By the way, “This American Life” did a brilliant episode on Middle School –- so insightful and entertaining. Please, by all means, check it out. You know I wouldn’t steer you wrong. You can access the full transcript, too.

You did steer me wrong once, but I called AAA and they got me out of that ditch.

Back to the main river: I think if you wrote about the later Mark Twain, it could have easily led to a tone that was too reverential, all hail The Great One, full of wisdom. But this way, Sam is as flawed and vulnerable –- as human — as Lee and Joan.

I love that Twain here frequently says to Joan and Lee, listen, I’m new to this whole time-travel thing, too, and I’m as clueless as you are. That’s a great thing to hear from an adult. I think it gives you more confidence in yourself at that age, and it also makes you feel like less of a freak. If I’d gone for full-blown Twain, the white-suited figure we all know, it would have become, I think, an exercise in bad down-home imitation. In early drafts of the novel, it was that, to an extent, and I had to work hard to resist it.

The book also serves as a love note to San Francisco. The city itself stands as an essential character.

I end up writing about San Francisco over and over again, and it’s always a love note. I’ve lived here twenty-six years now, and not a week goes by that I don’t look up and thank my lucky stars. But San Francisco is also a perfect setting for this book in particular because it’s a place people have always come to in order to become who they most want to be. There’s that freedom here, that license, if you will. It’s not a mistake, really, that it was here that Clemens found his Twain.

Yes, exactly. In the book, Miss Greta speculates on the question of why San Francisco? Why are these time-traveling incidents –- where some select few travelers get unstuck in time — — happening here, in this city, of all places. She tells Joan:

“There are other places we’ve heard about. But San Francisco’s a good one. Very popular that way. People come here to find their futures. You can be who you want to be here. Keep a remember on that.”

Keep a remember on that. Very nice. You love this city, don’t you?

I do love it, for its natural beauty and for the freedom of it. It’s been a true gift to raise my daughter, now 13, in this city, and see how that’s worked out for her personally, and how she views other people. Everyone here is a freak, in some way, an eccentric, which means of course that everyone is an individual and treats others with the same respect.

Obviously, you must have done a lot of research.

One of the great things about writing these books has been able to say, “Oh, I have to go work now,” and then settling down to read Steinbeck, or Dickens, or Twain. I mean, really, Work?

I was happy to come across a video interview with M.T. Anderson. He was asked about his typical workday and he talked about the importance of exercise –- that it was a perfectly valid, essential part of his day as a writer. And I need to be reminded of that permission, you know, that it’s okay to do yoga or take a walk or whatever, that it’s part of my job. So, thanks for that, M.T. (By the way, did I say “do yoga”? I meant, “lift enormous amounts of heavy weights.” I don’t want my Nation of Readers to get the wrong idea; I’m a very tough guy.)

Hey, for some of us, doing yoga is lifting enormous amounts of weight. Listen, writin’ ain’t coal-mining, let’s be clear on that. But it’s true, so much of a writer’s job — at least in my experience — takes place away from the desk. Staring out the window, taking walks, whatever. Writers are, Stein said, “those upon whom nothing is lost.” It’s part of the job. You look at everything, are interested in everything.

Huh? What? Are you still here?

Focus, focus. You take your ritalin this morning?

Look: a bird!

I’ve also become a rather devoted historical researcher — histories, biographies, fashion, technologies, and my favorite of all, maps. Whenever I’m working on a new novel, I’ve got tons of old maps pinned up over my desk, as if they were blueprints and I were just the contractor on the job. Building a whole city in your head and populating it. Work, indeed.

Joan discovers that taking a bath in 1864 was a major hassle.

Listen, no one really wants to go back into the past. Even for the wealthiest of the wealthy, they were mean and dangerous times. A simple infection could kill you, if you made it past childhood. These issues rarely come up in time travel, so I wanted to touch on that. The past? Great place to think about, but no thanks. I’ll stay here with hot showers and antibiotics. It’s silly to romanticize the past, which, at one time, of course, was the absolute present. One of the things Joan notices about SF in 1864 is how new it looks. To her 2012 San Francisco is sort of old and falling apart.

You take delight in the language of the times. “Sorry don’t milk the goat, “ Miss Greta says at one point.

I may have stolen that from Dr. Phil, I’m afraid.

Ha! We stand on the shoulders of giants.

But it also comes from steeping myself — again and again — in Twain, whose language just pops all over the place. I’ve got notebooks filled with expressions and words I just couldn’t fit in. My two favorite Twainisms that made it into the book — he uses these in both Huck and Tom Sawyer are, “Honor Bright,” a mild oath along the lines of “I’ll be,” and “Hang fire,” meaning it’s time to chillax.

Literally, to hang the lantern on a hook. Settle in. Hang fire.

I also had fun teaching Twain — who would have been curious to learn it — about the slang of Joan and Lee’s time. Lee teaches him how to say ”Dude” at one point, and “Freak out.”

You write powerfully about the discrimination experienced by the Chinese residents in San Francisco during the 19th century. The so-called “Chinese Menace” or “Yellow Peril.” For Joan as a fully assimilated Chinese-American to see it, and feel it, and by frightened by it, well, I just thought you brought that period home in a very real, hard-hitting way. Joan was the key to telling that part of the story.

San Francisco was a horrid place to be Chinese, for long, long decades, but now the Chinese community in SF is very powerful and very much the majority. These are my neighbors I’m talking about, my daughter’s schoolmates. This goes back to what I was saying about the past. Things have gotten better — slowly, slowly, but better.

In each of these books I’ve tried to bring in really urgent social issues: racial discrimination and violence in both Twain and Steinbeck, child labor in Dickens. It seems a disservice to any reader — young or old — to overlook these matters. And besides, that’s one reason we still turn to these three writers, their concerns for social justice, their unflinching attitudes toward our cruelties.

The book is also, at its heart, an old-fashioned adventure. Amidst all the research and big ideas, it’s important to remember that.

In the first draft, it was all adventure, all chase and struggle. My editor, Liz Szabla, told me time travel was really hard and I needed to be careful. I came to discover, through Liz’s editing, that I’d used time travel as a gimmick, when what I really wanted to do was write a book about time. That was hard. The adventure has to serve the bigger concerns of the book; a book that’s just car chases and gun fights is really only a lousy movie.

I think far too many books today aspire to only that, the dream that somebody in Hollywood will turn it into a lousy movie. Ca-ching!

I’m not saying I’m not interested in a movie deal. No chump, me.

No, of course, we’d all love to pay off the mortgage and get college squared away. Fame and glory on the red carpet with Brad and Angelina. However, there seems to be an increasing amount of books written as if, well, they were not intended for readers. Plot, plot, plot; frantically paced. I decided that, for me, the ultimate reader is someone who isn’t afraid of being bored. Like a baseball fan. That is, I have to trust that the reader is going to hang with me a little bit, because I’m not really set up to write every story like it’s a roller coaster ride. Does that make sense? I don’t plan on boring anybody, exactly, but I can’t be overly worried that I need a car chase in the next three paragraphs or my readers won’t turn the page.

I write, I believe, for people who like to read, who want to see the world in a slower, more engaged way. We have enough “fast” media in the world. Books are meant to be slow, which of course, takes away nothing of their excitement.

Lewis, don’t tell my wife, but I think I’m falling in love with you. Anyway! Almost midway into the book, Joan and Lee realize that this fellow they’ve been hanging around with, this Sam Clemens guy, is actually . . . Mark Twain, the famous author. I wondered about that a little bit, how many typical middle schoolers would know about Twain. Or care. And the great thing about BRIDGE OF TIME is that it’s incidental: Twain, the great author, doesn’t really matter. A reader doesn’t have to know a thing about him to enjoy this story.

Lots of middle schoolers will have read Tom or Huck already, though not most. However, when I visit middle grade classrooms I always ask about Twain, and most know something about him, or at least about Huck. The interesting thing about these writers — especially Twain and Dickens — is if you haven’t read the work you still know about them because they are such a part of the cultural currency. Yes, even in this iMac iMad world we live in. Bah Humbug. There you have it. I also chose each of these writers, however, with the hope of getting that one interested reader to move on to Steinbeck, Twain, or Dickens. This is the age, really, when kids will begin to read their first adult books, and these writers are perfect for that time.

Yes, we’ve touched on that topic before. How for readers of our vintage, there was no “YA” exactly, we just merrily went on to Steinbeck or Bradbury or Vonnegut or Brautigan. Then I guess S.E. Hinton came along, Paul Zindel, and others who became intensely interested in those earlier stages of life, the teenage years, and the publishers figured out there might be a market for it.

When I think of the best MG and YA writers, I don’t make any distinctions in age groups. For example, I’d put Virginia Hamilton’s PLANET OF JUNIOR BROWN up against any “adult” novel, and the adult novel would pale. Good writing is good writing: period. Alas, much of what gets published in the MG and YA niches is just dreck, plain and simple. But in this way, it resembles most of what gets published in the adult trade, pure dreck. This is as old as publishing itself.

I identified with an aspect of Sam Clemens, the part of him that was fearful, that lacked self-confidence, doubted if he was good enough. You know, I’ve really felt that all my life –- I feel that right now with the book I’m writing — and I’d bet that most artists have experienced those same doubts. Clemens is scared out of his mind, paralyzed, that he’s not up to the task of becoming the writer he always wanted to be. Is that something you’ve felt?

I feel it every day. I mean, no matter what I’m doing, I still feel a fraud, and that I might get caught out at any moment. Don’t we all feel that way a bit? And kids especially. But I never feel it more intently than when I sit down to write. From having read so many journals and biographies and letters, etc., of other writers, I’m convinced this is true of all artists. No matter how much I’ve written, when I sit down to begin a new project, I think, I have no idea what I’m doing. And this is good. If you set out knowing exactly what you’re doing, well, then you’re probably going to write something stale, without surprises. The poet Richard Hugo put it so gracefully: “Hope hard always to fall short of success.” It’s the doubt that makes you work harder.

Finally there comes a time when Sam must face his own future –- which is what the book is about, for all of us, daring to become our very selves. There’s a lovely scene between Joan and Sam. She recognizes the fear he’s experiencing. And Joan tells him what she believes Twain would say to him (Sam), if he (Twain), only could: “He would tell you that you must try. That you should cast off.”

Sam would not look at Joan.

“I am afraid to even try,” he said.

It was strange to see Sam this way, all the brash taken out of him. Deflated. But oddly reassuring, too. It made Sam seem more real.

“I am afraid of trying,” Sam said, “because I want so badly to be who I think I might one day be. And if I fail . . . I’ll have no future at all.”

We’re back to the doubt. You can be paralyzed by it, or you can recognize it and make the big leap forward. Kids, too, know that adults are often full of b.s., and can see through facades like x-ray machines. It’s just better for them to have it acknowledged. Sam’s doubt does paralyze him for a while, but in the end, it’s his doubt that propels him forward.

I have to say this. As a rule, I hate time travel. It never makes sense to me, and too often it’s handled crudely, non-sensibly. I mean, yes, there’s a conceit, as readers we have to take that leap of faith and go with it. But, but, but. It still has be remain credible –- the reactions, the motivations, even the science, to a degree — and I think you achieved that in the best possible way.

Time travel — which we believe to be impossible — is mostly a wish-fulfillment fantasy. If only I could have saved Lincoln . . . But I don’t believe the world can be changed that way. I do believe, however, that our awareness of time — through history and literature and other media — can give us a much clearer sense of ourselves. In the end, this is what I aimed for.

But, my goodness, it must have been complicated to write. No? I mean, just keeping it straight, keeping the internal logic in line with some kind of familiar reality. Was there a lot of revision?

Oh lord. There were long chapters in the early drafts — I did five MAJOR revisions of this book — where Lee and Joan and Twain just sat around talking about time and how it worked. It took me forever to get it down to just what I wanted. And finally the answer came from Twain. In the book, Sam talks about the Mississippi and how sometimes it’s so large, you think you’re still on the river but you’ve really gone into a side channel and you’re away from the main current, often for miles. That’s what Sam says to Joan and Lee about Time Travel — it’s just a diversion, one that gives you a better view of the real thing, and in the end, you’ve got to go back to the main current. That’s where life happens.

I see that you dedicated the book to your editor, Liz Szabla.

Liz took a huge chance on me with STEINBECK’S GHOST, buying it on a proposal, and then when that was done, took another chance on these ideas about Dickens and Twain. Really did change so much for me. Not only is she a brilliant editor — meaning she see through to the essential heart of a story and leaves behind the silly “market” questions, she offers what writers really need, the sense of support. Publishing a book hardly ever “changes” your life in some miraculous way, but it does give you the support you need to go on, write the next one. She’s the rarest of editors.

Agreed. We’re very, very lucky to have her on our side. You know, my hair bristles when I hear complaints about messages in books. As if that’s a bad thing, or an avoidable thing. I contend that you can’t tell a story without values and messages embedded throughout. The issue is one of craft –- how artfully these messages are delivered. And in this book, one message can be reduced to two words: CAST OFF. “Have fun. Look around. It’ll be okay.” Dare to dream. Or as Maurice Sendak ended his recent interview with Terry Gross on Fresh Air, “Life your life, live your life, live your life.”

There’s a huge difference between a message and a moral. Messages are deeper, more subterranean, closer to the heart, unsaid. Yes, Twain does come out and say it, but it seems almost frivolous at the time. What better message could there be? It’s what friends do for one another, offer that permission and challenge.

Good distinction. Joan again seems to get the deepest thoughts:

“Joan no longer believed what Sam had said, back on the Paul Jones, about lessons and morals and how they could ruin an exciting adventure. She now firmly believed, from her own experience, that the best adventures offered you lessons, no matter what. If not, an adventure was just a roller coaster ride. An amusement. A true adventure, Joan realized, took you places –- or times –- you could not have begun to imagine. Always something to be learned in the unknown.”

If a book is true to life — and not just some pre-fabbed fantasy world—then there have got to be lessons — or messages. A book is a way for the reader, I think, to examine the world deeply and courageously. Or at least a way of finding that courage. I read books because they talk about the world, and when I’m done, they make me want to go out into it.

Do you have a favorite part of the book?

There’s a scene where Lee and Joan and Twain, while being chased, take a small sailboat out onto San Francisco Bay, and I think it’s my favorite bit of prose ever. The danger of the pursuit has passed, but the danger of the black water is still there. I like that.

While the flames from the Paul Jones licked into the night sky, Sam unfurled and hoisted the sail, and a soft southerly breeze caught and inflated it. The boat jerked once, then set off gliding over the black water.

Lee stared forlornly after the Paul Jones.

The waning moon offered enough light to enchant the night. The bay was black but visible. It was perfectly quiet out here, and Lee was happy with that.

They emerged from their sheltered cove into the open bay, and a stiff wind caught the sail. It felt to Lee as if a hand was pushing the boat from behind.

Up ahead was the black silhouette of Yerba Buena Island, partway between San Francisco and Oakland. Where the Bay Bridge and the man-made Treasure Island was supposed to be.

As the boat came even with the southern tip of Yerba Buena Island, a sharp hissing noise filled the air. But before Lee could turn, three sleek sails hove into view on their starboard. The three boats were longer and thinner than Sam’s old clunker, and their sails were enormous. The boats rode low in the water, the sails tipped so far over they etched the surface of the bay. One dark shape manned each tiller.

You write beautifully, Lewis. And readers should know that the above passage came on the heels of a tumultuous scene with butchers, cleavers, shotguns and burning ships (are you listening, Hollywood?!). The veritable calm after the storm: Expertly paced. My old friend, the great Scholastic editor Craig Walker, used to say that the best thing Twain ever did was get Huck out on the water. Because then it was all there, the physical liquid space, sliding through the solid world, but also floating on literature’s richest metaphor: water -– of consciousness and time, currents and dangers, life’s eddies and so on.

That’s why Huck is Huck. He’s out on the water, watching the placid, unchanging towns go by. You get a better view of the world from there, and you’re going some place, changing with the world as it changes you.

Lewis, thank you for giving us this beautiful, inspiring book. Look, as you know from my private complaints, I’m often brutally dissatisfied with children’s books. There are so many that I find to be cynical, commercial, copycat, disappointing. And, yes, the counterpoint holds true: many are rich and wonderful, the best books imaginable. With the BRIDGE OF TIME, I declare you on the side of the angels. I respect and admire what you’ve achieved here. Because you wrote an adventure, a fun story, but also a story that is deep, that has meaning, and heart, and enduring value. It’s the genuine article. I wish for this book to find the audience it deserves –- and earn some starred reviews in the process. Good luck to you, Lewis. And now, if you’ll excuse me, I must . . . cast off.

James, all I can say to such praise is, “the check’s in the mail.”

Forget that, Lewis. My dream is to make it out to the Left Coast someday. Catch a baseball game, watch Timmy pitch, and chat our way through nine innings.

You’re on. We have the best garlic fries in the league, and Gulden’s Spicy Brown mustard for our dogs. Or we can even go for free. Part of the right field fence at AT&T has a clear view from outside the park, and anyone can go there and watch the game in what we call The Arcade. I think that’s where writers belong anyway, outside looking in.

—–

If you enjoyed this interview, please check out my 2009 interview with Lewis, back when he was a hirsute middleweight, boxing under the name Louie “The Buzz Saw” Buzbee. The interview is in three parts, it’s lively and fun and features a taser.

Want to see Lewis on television? Sure you do! Click here for a nice interview, based on his wonderful book, THE YELL0W-LIGHTED BOOKSHOP.