–

“When I started, I had no idea

what the poem was going to be about.

I just followed the words home.

Sometimes that is the best journey

a writer can experience.”

— Vikram Madan

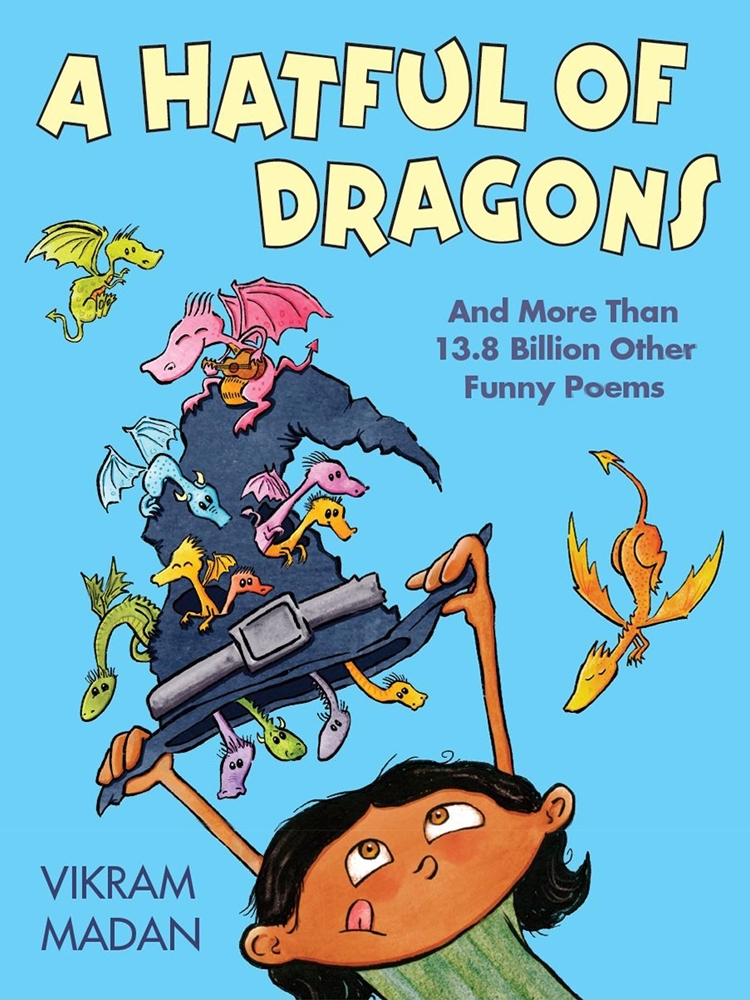

I’m that guy at the party — do you remember parties? it was this thing in the olden times when people used to get together and — nevermind! — I’m the guy who tugs on your arm and says, “Have you read Vikram Madan’s new book? It’s fantastic,” and then I press it into your hands. Anyway, today we’re lucky to spend time with debut children’s poet, Vikram Madan. His clever, quirky, playful poetry includes aliens and garden gnomes, robots and dragons, instantly bringing to mind past masters Shel Silverstein and Jack Prelutsky. So put down the Swedish meatballs and let’s say hello . . .

–

Greetings, Vikram. Congratulations on your new book!

Thank you, it’s a pleasure to be featured here!

I’m curious about the path that led you to this moment, a collection of playful poems for young readers. According to your bio, you spent many years working in the tech industry.

I grew up in New Delhi, India and was rhyming and doodling from an early age but never imagined myself as an artist or poet. Instead I followed the herd into engineering and ended up working in tech, with one brief detour as a newspaper editorial cartoonist. It was only after my kids were born that I encountered the work of Dr. Seuss, Shel Silverstein, and Jack Prelutsky and that inspired me to start writing poetry again, though it took me the next decade to figure out how not to do it.

Wait, how not to do it? What mistakes were you making?

I was writing rhyming poetry very instinctively, and it was largely raw –- forced rhymes, mismatched stresses and pauses, unbalanced and asymmetrical feet, lines that wouldn’t scan cleanly -– basically everything that makes an editor wince. Sometimes I could tell it was off, but not why. Only after discovering prosody did I develop the vocabulary to analyze what I was doing, and fix what I was doing wrong. For those interested in writing rhyming poetry, I highly recommend Timothy Steele’s All the Fun’s in How You Say a Thing. By 2012 it was clear to me that I needed to ‘follow my heart,’ at which point I quit tech, enrolled in art school, and started writing humorous poetry, all of which has culminated in this book.

–

–

Bold move, Vikram. There’s a great tradition of poets and their day jobs. Wallace Stevens worked for an insurance company; William Carlos Williams was a general practitioner; Frank O’Hara worked as a clerk and published a collection titled, “Lunch Poems.”

I think most poets have had to have day jobs. Poetry is a labor of love and feeds the soul, but rarely the stomach :). Right now my day job is ‘visual artist’ so I suppose I am a little more fortunate that I can scratch my creative itch in more ways than one.

With A Hatful of Dragons, you were published by Boyds Mills & Kane. But you self-published your first book, The Bubble Collector. People have differing perceptions of self-published work, but I think it was a courageous step. Big respect. Tell us about it.

With A Hatful of Dragons, you were published by Boyds Mills & Kane. But you self-published your first book, The Bubble Collector. People have differing perceptions of self-published work, but I think it was a courageous step. Big respect. Tell us about it.

Poetry is fairly hard to place with agents and publishers, and a common submission guidance is “Don’t tell us your work is just like Shel Silverstein’s,” which was a problem, because my work is like Shel Silverstein’s! After years of amassing rejection slips, I finally decided that if no one was going to publish my poetry, I would just publish it myself, which led to The Bubble Collector. Once the book was out, I discovered writing a book is the easy part. Getting a physical self-published book in front of readers is HARD. By ‘hitting the pavement’ a lot, I was able to get the book in front of enough people that it was invited into the WA State Book Awards, won a Moonbeam Children’s Book Award, and garnered praise from booksellers, reviewers, and readers. The experience, though, gave me a healthy respect for traditional publishing!

Are there particular poets who influenced you? When it comes to funny poems for children, I guess Jack Prelutsky sort of owned that playing field for many years.

I didn’t believe I could write poetry professionally till I saw an exhibition of ‘raw’ Dr. Seuss manuscripts. I didn’t think of combining art with words till I encountered Shel Silverstein’s books. And Jack Prelutsky’s work opened my eyes to language, vocabulary, rhythm, and rhyme. Beyond those three, I particularly admire 19th century poets: Lewis Carroll, Guy Wetmore Carryl, W.S. Gilbert, John Godfrey Saxe, and Edgar Allan Poe.

–

It’s interesting that you illustrate your own poems. Who is the boss, the writer or the illustrator? Or does the inspiration flow back and forth? I’m fumbling to ask: Do you start with the words or an illustration?

It depends and is different for each poem. Sometimes I conceive the art and words together, sometimes the words are in the driver’s seat, and, occasionally, a visual image will trigger the poem. Usually as I am writing I do have a good sense of how the combination will look on the page.

I imagine that your process changes from poem to poem. I wonder if we could share a specific poem from the new book here, and then you could talk us through your creative process.

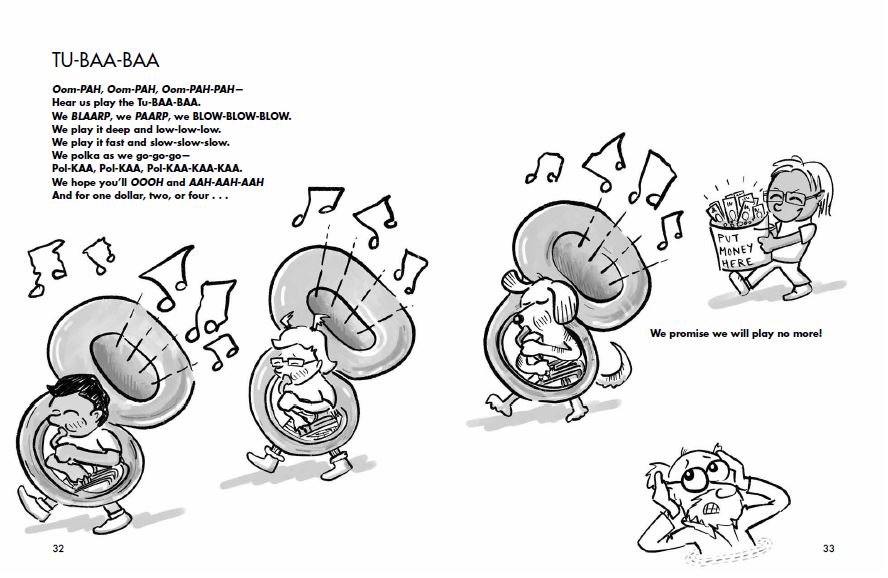

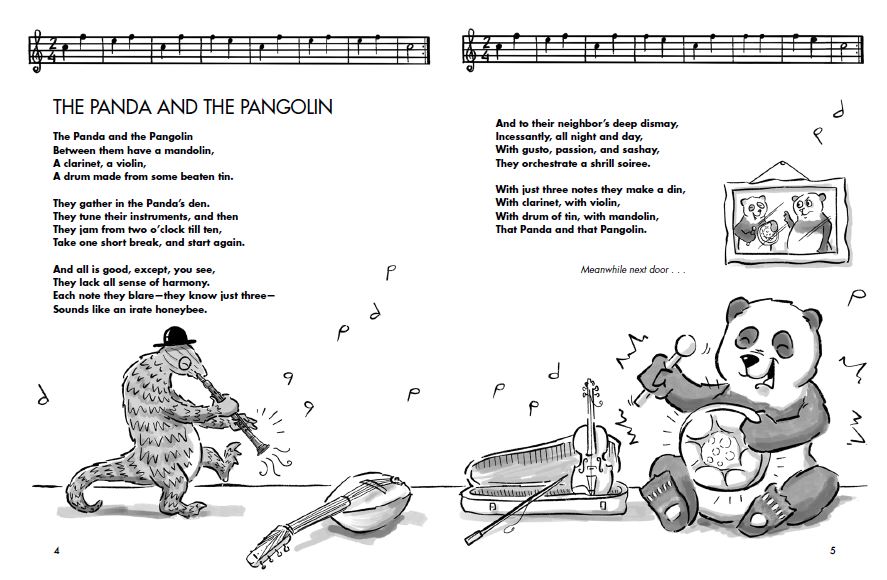

Yes, every poem has its own unique back-story. When I am writing poetry, the natural cadence and in-built rhythm of words, both in how I hear them and how they feel on my tongue, can sometimes organically steer the poem one way or another. An example of this is the first poem in my book, “The Panda and the Pangolin.”

–

–

Looking back at my notes, I had been making lists of animals as potential subjects, and at one point I wrote:

Banded Pangolins

followed by:

A band of banded Pangolins

And following the sound of that sentence, I then wrote:

The panda and the pangolin

which seemed to offer more possibilities.

You are fooling around with language, alert to the inner dynamics, without necessarily an end in sight.

Yes. I asked myself, What if it was the other way around?

The pangolin and the panda?

I tried:

At the edge of my veranda

sat a pangolin and panda

But “The Pangolin and the Panda” didn’t have the same natural rhythm as “The Panda and the Pangolin,” so I went back to the original:

Said the panda to the pangolin

I like your little mandolin

Better. And it was developing a musical theme, similar to the “band of banded pangolins.” But I needed to drop the extra “Said” syllable:

The panda and the pangolin

between them have a mandolin

a clarinet, a violin

a drum made from some beaten tin

And the rest of the poem unfolded from that starting point. The first poem then directly seeded the next poem, which then seeded more humor in other parts of the book. Note that, when I started, I had no idea what the poem was going to be about. I just followed the words home. Sometimes that is the best journey a writer can experience.

Delightful! Thank you for sharing that, Vikram. It’s been a pleasure getting to know you and your work.

Thank you for featuring me here. It’s an honor!

Hey now, don’t get carried away. Glad to have you, and good luck.

–

–

Vikram Madan grew up in India where, despite spending his childhood rhyming and doodling, he ended up an engineer. After many years of working in the tech industry, he finally came to his senses and followed his heart back into writing, drawing, and painting. When not making whimsical paintings and public art, he writes funny poems. His self-illustrated poetry collections include A Hatful of Dragons and the Moonbeam Award Winners The Bubble Collector and Lord of the Bubbles. He lives near Seattle, Washington, with his family, two guitars, and a few pet peeves. Visit him at vikrammadan.com.

Vikram Madan grew up in India where, despite spending his childhood rhyming and doodling, he ended up an engineer. After many years of working in the tech industry, he finally came to his senses and followed his heart back into writing, drawing, and painting. When not making whimsical paintings and public art, he writes funny poems. His self-illustrated poetry collections include A Hatful of Dragons and the Moonbeam Award Winners The Bubble Collector and Lord of the Bubbles. He lives near Seattle, Washington, with his family, two guitars, and a few pet peeves. Visit him at vikrammadan.com.

–

–