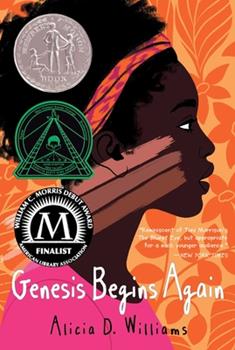

When I first read The Talk, I instantly knew that I wanted to highlight that book here. And I definitely wanted to learn more about (and from) author Alicia D. Williams. When Alicia began this process with me, she was already the author of a Newbery Honor Book (Genesis Begins Again). Then on Monday, less than a week after we’d finished swapping emails, The Talk was named a Coretta Scott King Honor Book. Pretty good.

–

–

But before we get to the actual interview, allow me to break format and share this email exchange that I had with Alicia.

–

I wrote:

–

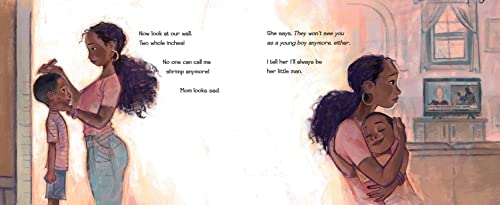

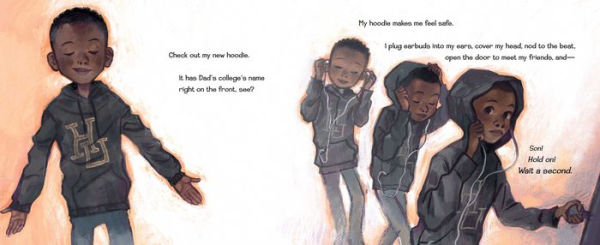

Thank you for showing me the grace of time. Yes, the talk is very uncomfortable. It’s uncomfortable and heartbreaking to give as a parent. And the conversation isn’t a one and done conversation either. It happens every time a situation occurs that needs to be addressed, a new event that needs to be talked about, when traveling or sending your child out with friends. And I get being uncomfortable with the illustrations as a white representing person. I wanted the average white reader to question themselves, their biases, and stereotypes that they subscribe to. I want them to be aware of the “look” so when someone around them is giving the look, then they can tune into the uncomfortable feeling and hopefully be an ally. I’ve gotten that look way too many times and even just recently when my car was stopped in a mall shopping center because I “looked like I needed help.” As part of the work of making our world more equitable, we all need to be more comfortable with being uncomfortable, as diverse leaders say.

–

–

–

1) Hey, Alicia. I wonder if you could please tell us something about your childhood?

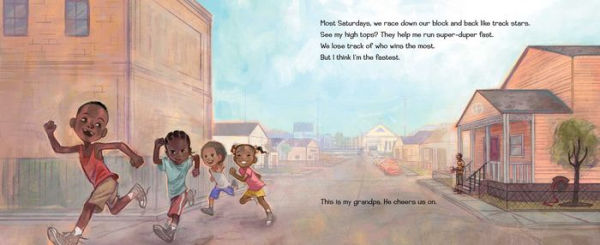

I grew up in Detroit, Michigan. We moved around a lot, so it was always a challenge to make friends, especially since I was a quiet, shy kid. And chubby. Fat shamed too. So, these things made me go inward. I would rather be curled up in a corner reading a Judy Blume book. Or spinning records on my record player while pretending to be a radio deejay. Back then, children played outside all day until the streetlights came on. Sometimes I would try to tag behind my brother as we sped through the neighborhood on our bikes, but I couldn’t keep up with him or his friends. Many times I’d be at my grandparent’s house which provided stability, so I had friends to look forward to. We’d go to the corner laundromat and play the pinball machines or my favorite video games, Centipede and Galaga.

I wish I discovered my voice or was given permission to speak my mind as a kid. If so, when presented a chocolate bunny award for our third-grade egg decorating contest, I would’ve asked for the coloring book and crayons instead. In fourth grade, I would’ve tried out for the school play, The Wizard of Oz. In fifth grade, I would’ve asked the teacher why she only let boys color the banners that hung in the hallway and never girls, and that I was an amazing colorer.

But no, I was a decent, quiet student. Well behaved. There was nothing special about me, but I always knew I wanted to be special. As a little girl I used to pray, I want to do something that will reach the masses. I had no clue what that would be. Probably didn’t understand the prayer in itself. But I knew, deep down, that I wanted to do something great in life.

–

2) My goodness, The Talk. What a powerful, empowering, profound and yet incredibly sad book. I’m aware that “the talk” is a real thing, quite outside my own childhood (and parenting) experience. When and why did you decide to try to make it into a picture book for young readers?

Thank you.

The subject of “the talk” has been in my mind for several years. Yet, I didn’t think I should write the story because of potential blind spots as a woman. I held no experience living as a Black male nor had I raised one. But I raised a girl and knew my worries were almost the same. I gave my own daughter the talk when shopping, when she got her driver’s license, and when staying at AirBnB’s. Still, I tried to give the story away to male peers. Even tried to enlist a male poet to co-write it specifically as a picture book because I envisioned it to be a poetic conversation like poet Dudley Randall’s poem Ballad of Birmingham. Eventually, I let it go figuring the story will ride the wind and land at the hands of the right writer.

–

–

In 2020, I, along with so many others, was deeply impacted by George Floyd’s and Ahmaud Aubrey’s murder, as well as the last words of Elijah McCain. I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t focus. But one night when I did manage to rest, a little chatty voice woke me and wouldn’t let me rest until I grabbed a pen and paper. The boy, the character Jay, introduced me to his friends, family, and everything he was proud of. Those same moments of pride came with a warning or a talk. The story literally unfolded that night.

–

–

3) A lifetime to experience, years to ponder, and a night to write. Sounds about right. As a writer, you are a believer in the bad first draft. Or, at least, the imperfect one. How does that self-permission help you move forward with the work?

It is easy to talk about the idea of writing a bad draft, of just letting go and write. But it is so so much more difficult to actually practice it. For me, it takes many starts to let go and finally give myself that permission. But once I do, I keep pushing myself to just keep going. Mentally, I have to repeat a mantra very similar to Dora from Finding Nemo . . . just keep swimming, just keep swimming. And even then I may struggle. I am still learning my process. And each book requires a different process in how it wants to reveal itself to me. I think the biggest thing is learning to be gentle with myself. That’s just as important as coming to terms with imperfection.

–

–

4) Your Newbery Honor Book, the novel Genesis Begins Again, took years for you to write and rewrite and rewrite. It was especially interesting to me, because I think it’s such a primary lesson for all writers, in that you started with a story that was closely autobiographical. But over time, you were able to pull back and fictionalize the story. Could you tell us more about how that process developed for you, and what that distance gave you as a writer?

The story began in graduate school. And yes, the whole “write what you know” came into play. I knew about a girl who had been bullied and who didn’t believe she was lovable because of the way she looked. And yes, I borrowed a lot from my life, initially. Then I realized that my ego controlled the story as I retold scenes as they occurred. This made the story feel forced, and well, dated.

The only solution was to divorce myself from the story; give Genesis her own voice. Once I did this, the story became much more interesting. Genesis took risks that I would never have. She said things that I would have never said aloud. I was able to put Genesis in trouble and not rescue her. As one of my teachers said, “No trouble, no story.” Once I did this, I let Genesis figure out solutions on her own—even if she made a mess of things. With each revision, I discovered more layers for Genesis and the other characters. With each revision, the characters began to speak to me and dictate how they would react and act in different scenes and events. If I didn’t listen, my editor would catch it and make a small note that read “authorial.” And I knew that it was me who was speaking and not the characters themselves.

–

5) You recently wrote poignantly on social media about your father, who is no longer alive, and imagining him saying all the things he never got a chance to say to you. Looking at you now, and considering the beautiful & important things you’ve already accomplished, what do you think he’d be most proud of today?

–

–

Oh, wow. I have never really thought of what he’d say. But now as I think about this—okay, I’m about to be vulnerable in this moment—I think my father would be proud that I love and parent my daughter in a way that he wasn’t able to (show) love and parent me. And I truly believe he would be proud, that with all I’ve gone through in my childhood, I am honoring myself and the prayer that I whispered as a child to “reach the masses.”

You’ve done good, Alicia. It’s been a pleasure to have you visit here. My hope is that educators will use The Talk with learners of all ages to initiate conversations that are open, honest, thoughtful — and yes, even uncomfortable — in classrooms across our great and troubled land. Thank you for that. I’m sure that somebody’d be awfully proud.

–

–

JAMES PRELLER is the author of the “Scary Tales” books and the popular Jigsaw Jones mystery series. He has also written middle-grade novels, including: Bystander, Upstander, Blood Mountain, Better Off Undead, Six Innings, The Fall, and Courage Test. Look for the first book in his strange & mysterious middle-grade series, EXIT 13: The Whispering Pines, available in stores in February 7th, 2023. The sequel, EXIT 13: The Spaces In Between, comes out in August!

JAMES PRELLER is the author of the “Scary Tales” books and the popular Jigsaw Jones mystery series. He has also written middle-grade novels, including: Bystander, Upstander, Blood Mountain, Better Off Undead, Six Innings, The Fall, and Courage Test. Look for the first book in his strange & mysterious middle-grade series, EXIT 13: The Whispering Pines, available in stores in February 7th, 2023. The sequel, EXIT 13: The Spaces In Between, comes out in August!

–

I really appreciate you highlighting this book and the author. Such important work and a book that I will purchase!

I especially liked how Alicia separated herself from the character, Genesis, in order to write the final drafts. Yet what a wonderful way to begin a book that matters to you–from the inside out.

Thank you for this interview!