–

The first time I met Nina Crews, I was eating on the hallway floor of a school in Albany, NY. Just sitting there on the tiles, catching a few minutes for lunch during a book festival. Nina sat down across from me and, putting two and two together, I asked, “Are you the daughter of Donald Crews?” We had a nice chat that afternoon; a number of years passed; and now with the publication of her quietly remarkable book, Seeing Into Tomorrow, I reached out to Nina again. She’s an easy person to like, an artist with a deep commitment to children’s literature. I don’t have a powerful spotlight here at James Preller Dot Com, but this is an artist who merits our attention.

Here comes Nina now . . .

–

Congratulations on your new book, Seeing Into Tomorrow. I’ve been waiting for this one since we first discussed it via Facebook about a year ago.

Thanks so much! I am so happy to have it out in the world!

Lately I’ve been on a major haiku kick of my own, reading and writing a little bit each morning. I’ve been reading through a collection of more than 800 of Richard Wright’s haikus. I enjoy taking them slow, savoring each poem, just a few pages before I start the day. I originally took Wright’s book out of the library, but soon realized that I needed to have my own copy, write in it, keep it on my shelf. How did you select the poems included here? That seems like an impossible process.

I know the Wright book very well! It was the source for the haiku included in my book. I read through it numerous times and also used a lot of post-its. Each review brought new discoveries, and also helped me clarify the direction of the project. There were really two main criteria that a poem had to meet for me to add it to my shortlist. First, I looked for poems that could resonate with children emotionally and second, for poems that could be portrayed through relatable everyday scenes.

I know the Wright book very well! It was the source for the haiku included in my book. I read through it numerous times and also used a lot of post-its. Each review brought new discoveries, and also helped me clarify the direction of the project. There were really two main criteria that a poem had to meet for me to add it to my shortlist. First, I looked for poems that could resonate with children emotionally and second, for poems that could be portrayed through relatable everyday scenes.

I’m moved by the idea of Richard Wright turning to haiku late in his life, at a time when he was struggling through a long illness, sliding toward death. I sense that the process of writing these poems –- and seeing the world through them — comforted him. There’s terrible beauty in these poems.

Yes. I know what you mean. It was also a period of mourning for him. His daughter writes in the introduction to the haiku book that two close friends passed away in 1958. Even more significantly, his mother died in 1959. I imagine these losses put him in a very reflective mindset. His daughter calls his writing of haiku “self-nurturing.”

That’s a nice phrase, much better than “self-medicating.” With haiku, like yoga in a way, I believe the experience of writing them, of being present in the world, is more personally meaningful than the end product. Anyway, Nina, tell me about your cut-up approach to the photographs. I’m not a visual artist, but I used to fool around with that technique years ago, inspired by the work of David Hockney. It’s a lot of fun.

–

–

I am a fan of David Hockney’s photocollages and studied them closely while I was working on this book. For the most part, my images were not created by cutting up a single image, but by closely cropping the scenes as I photographed. I’d start at one end of a scene and move my camera, over bit by bit, up and down, to the left or to the right to cover the entire area. I liked the movement that this technique created and wanted the additional variation that would come from shifts in perspective or focus as I moved around. If you look closely at Hockney’s images, you’ll see that he does this, too. I think it gives the final image a bit more “breath.”

Oh, I get it now. I assumed it involved scissors, a lot of cutting and snipping and pasting. Why did you feel that approach was right for this book?

I read a great essay about haiku that talked about how the poems should have a sense of movement in them. There are a number of ways one can show movement in photography –- motion blurs or sequential images for instance. This approach is another way of showing movement and I liked how shapes of the collage could create a gesture on the page with the child portrayed acting as an anchor.

I appreciated how the book begins with a haiku about a name written in the snow, which to me is a declaration of existence, “I am” . . . and how a signature returns later in the book . . . and you close with a hopeful vision of, or for, tomorrow. Nicely curated, Nina.

Thanks!

You focused your camera exclusively on African American boys for this book. Why boys?

–

–

There were a few things that factored into this decision. Early on in my work on the book, I read Black Boy, Wright’s autobiography. In it, he describes how he experienced nature as a young child and the language he uses in those passages is similar to the language in his haiku. My exploration of  these poems became an exploration of Wright’s biography and photographing African-American boys made sense to me. It also struck me that there are not a lot of “nature” books with children of color, in general, and African American boys, in particular. I am pleased to give this “picture space” to young brown boys.

these poems became an exploration of Wright’s biography and photographing African-American boys made sense to me. It also struck me that there are not a lot of “nature” books with children of color, in general, and African American boys, in particular. I am pleased to give this “picture space” to young brown boys.

Am I right in recognizing Prospect Park, in Brooklyn, in some of these images.

Yes. I did photograph some scenes in Prospect Park. It is really an extension of my studio. Because the images for this book really depended on the right light and the right weather, I took advantage of every opportunity I had to get shots I might use. I also photographed extensively in upstate New York – Bear Mountain and the Hudson Valley.

You dedicated this book to your family. You certainly have talented parents, in Ann Jonas and Donald Crews. No pressure, Nina, just be amazing!

Yes, they set a high bar. They also provided a lot of support and have been great role models. But beyond my parent’s role in my development as an author illustrator, I feel a great deal of gratitude to my family for many less tangible lessons. For instance, I am thanking my grandparents who told me about their childhoods on farms in the South and my parents for taking my sister and I on many walks in nature.

Yes, they set a high bar. They also provided a lot of support and have been great role models. But beyond my parent’s role in my development as an author illustrator, I feel a great deal of gratitude to my family for many less tangible lessons. For instance, I am thanking my grandparents who told me about their childhoods on farms in the South and my parents for taking my sister and I on many walks in nature.

That’s your father, isn’t it, admiring the freight train. I see what you did there, since his book, Freight Train, was a Caldecott Honor Book. He always brought a great sense of design to his work.

Yes, I asked my father to do a cameo for this page. It’s a nod to his work -– Freight Train and Short Cut and also inspired by the fact that he enjoys watching trains with his grandchildren. That’s my son with him.

–

–

I actually interviewed your father many years ago, in the early 90s, for a book I did with Deborah Kovacs, the out-of-print classic, Meet the Authors and Illustrators. He struck me as a calm, gentle, elegant, highly-cerebral kind of guy. I picture him in a bowtie.

He owns many bowties, though does wear standard neckties as well. He’s very stylish and one of my favorite people!

Well, Nina, I’m really glad we were able to share this time together. You have a lot to be proud of with this beautiful book. Well done!

Thank you! I have enjoyed our chat!

——-

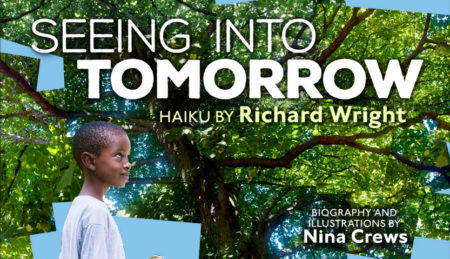

To learn more about Nina Crews, visit her website. Nina’s book includes substantial biographical information on Richard Wright, adding depth and layers to a reader’s experience of the poems.

To explore more interviews in the award-winning (not really) 5 QUESTIONS series, click here and scroll, baby, scroll. You’ll find interviews with London Ladd, Matthew Cordell, Bruce Coville, Lizzy Rockwell, Aaron Becker, Elizabeth Zunon, Robin Pulver, Jeff Mack, and many more.

A recent edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary swapped nature words for modern terms. Out went acorn, wren, dandelion, nectar, and otter. In went blog, bullet-point, attachment, chatroom, and voicemail. Updating dictionaries isn’t new. And maybe cygnet isn’t as relevant as database, but it’s certainly more musical. If we treat language like paper towels, it’s no wonder many kids can’t name common backyard birds.

A recent edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary swapped nature words for modern terms. Out went acorn, wren, dandelion, nectar, and otter. In went blog, bullet-point, attachment, chatroom, and voicemail. Updating dictionaries isn’t new. And maybe cygnet isn’t as relevant as database, but it’s certainly more musical. If we treat language like paper towels, it’s no wonder many kids can’t name common backyard birds.