The end of summer? Oh, let’s call it the beginning of autumn.

I’m excited to embrace the daily routine, my kids at school while I quietly hum along downstairs. We break out the sweaters, play soccer and baseball, rake leaves, build fires in the backyard, clean the gutters one last time, throw an extra blanket on the bed.

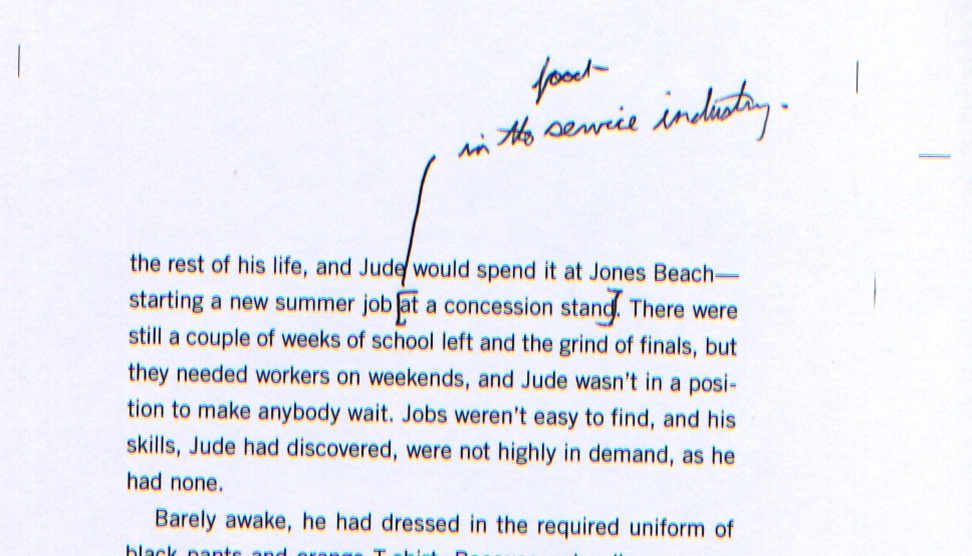

Blog-wise, I’m eager to get going on a lot of projects. I want to start talking about Bystander in earnest, background stories and such. That begins today, below. Honestly, I have notes for dozens of potential topics. I want to attempt a series of posts on “How to Plot a Mystery,” since so many teachers seem to work on that in the classroom. I’ve found some amazing videos to share, want to talk about books I’ve recently read (The Grapes of Wrath, In Fed We Trust, What the Heck Are You Up To, Mr. President?, Columbine, Swordfishtrombones, The Hunter, etc.), so many things to discuss!

Anyway, a cyberpage has turned. I’m energized and enthusiastic. I’m finishing a manuscript this week and starting another immediately.

Let’s talk about smiles . . .

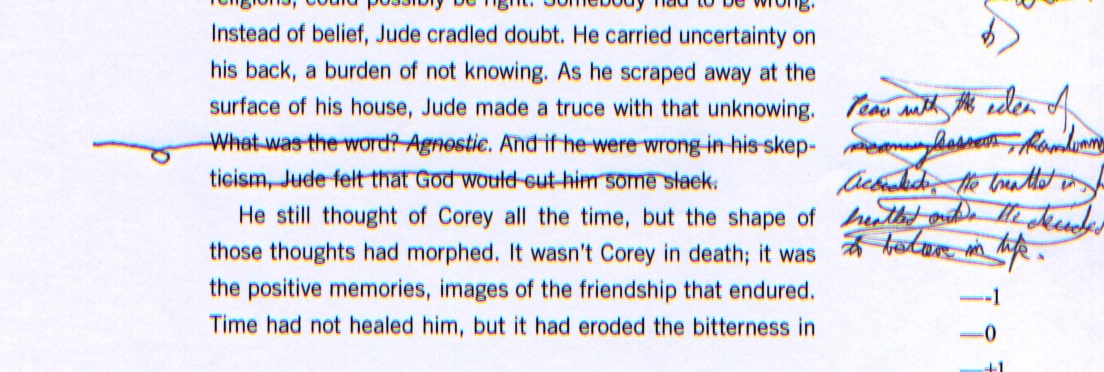

I began my work on the book that would become Bystander by hanging out in the local library with a composition notebook. At the top of the first page of that notebook I see that I copied a line from Michael Connelly’s Echo Park: “What is the bad guy up to?” I was excited. After writing 30-plus Jigsaw Jones mysteries for younger readers, I finally had a bad guy. It wasn’t going to be all benign misunderstandings and well-intentioned foul-ups; here, I had a character with potential for real darkness.

I see that I was reading Savage Spawn: Reflections on Violent Children, by Jonathan Kellerman. A powerful, disturbing book that looks at antisocial youth, from aggressive bullies to cold-hearted killers.

And right there on that first notebook page I started a list of potential “bully” characteristics. I wrote:

Smart, charismatic, charming, popular, superior, tortures animal?, trouble with police?, lights fires, COLD, raised by grandmother?, non-compliant, poor grades, not affected by discipline, causes fear, lucid, psychopathic?, free of angst, free of insecurities, (later, when caught, self-pity), preternaturally CALM.

I was in the first stages of character development — and for me, I’m at my best when character evolves into story, as opposed to plugging character into plot. That is: character first. With my focus exclusively on this “bad guy,” I even came up with a potential book title: Predator.

It became important to me that my main antagonist, Griffin Connelly, was divorced from the bully stereotypes we often see in books and movies. You know, the bully as gross coward, unlikeable lug, dim-witted brute, dirty, ugly, unpopular. It simply wasn’t realistic, and by turning bullies into one-dimensional characters, we surrendered much of the complexity (and difficulty) of the topic (and story).

A quick plea: There’s a tendency to slot any topical book, such as this, into the bibliotherapy shelf. But Bystander is a story, a page-turner with thriller elements that a biased Jean Feiwel called, “Unputdownable.” It’s not a thesis paper. It’s a good, fast read. I hope boys find it.

Whew. I see that I’m letting this post get away from me, because I’m trying to talk about too much. So I’ll get specific:

I wanted Griffin Connelly to be a great-looking kid, with charm and verbal dexterity and a great smile. He would be, in every sense of the word, attractive. All the surfaces would shine. The ugliness concealed.

His smile was one of the keys to his character. But what is a smile if not a baring of teeth? The smile beams beatifically, but also represents a flashing of fangs. A threat. The wolfish grin. There’s menace under the surface.

Griffin Connelly was the kind of person who would smile at you while he stuck a knife in your back. And maybe, for pleasure, gave the blade a twist. The toothy smile was the mask he wore, this master of the mixed message.

Page 7, when Eric first meets Griffin:

The shaggy-haired boy in the lead pulled up right in the middle of the court, halfway between the foul line and the basket. He stayed on his bicycle seat, balanced on one leg, cool as a breeze. The boy looked at Eric. And Eric watched him look.

His hair fell around his eyes and below his ears, wavy and uncombed. He had soft features with thick lips and long eyelashes. The boy appeared to be around Eric’s age, maybe a year older, and looked, well, pretty. It was the word that leaped into Eric’s mind, and for no other reason than because it was true.

Some random examples now . . .

Page 11:

Words came easily to Griffin, his smile was bright and winning.

Page 18:

Griffin flashed a smile, that hundred-dollar smile he could turn on in an instant. He reached out his fist. “Are we cool, buddy

Page 50:

“Mrs. Chavez!” Griffin exclaimed, smiling cheerfully. “Please let me help you with that . . .”

Page 68:

There was no way Eric could tell Griffin Connelly that story. So he told bits and pieces and white lies. Eric wondered if Griffin sensed it, the whole truth, if somehow Griffin already knew, saw into Eric’s secret heart and smiled.

Page 78:

“You want to hang out, don’t you?” Griffin asked. He smiled, put an arm around Hallenback’s shoulder.

Page 130:

Griffin winked at Eric. Then gave that big Hollywood smile, and swept the hair from his eyes.

Page 130:

“What are you going to do? Punch me?” Griffin taunted, grinning.

Page 131:

“I’ll be seeing you around, Eric,” Griffin said. His smile was like a pure beam of distilled sunlight. His long lashes blinked, his cheeks pinkened. He wore a perfect mask of kindness and light.

Page 165:

Griffin smiled wide, folded his hands together, and said in a soft voice, “We’ll see about that.”

Page 186:

Griffin grinned through the insults.

——-

Presented in this way, it may seem a little much. But in the context of the story, I suspect it’s unnoticed. The accumulated effect, I hope, is creepiness. Here’s a guy you can’t trust. Every threat comes with a smile. White teeth gleaming in the sunlight, fangs bared.

“My Grandma, what big teeth you’ve got?”

Don’t let that smile fool you.