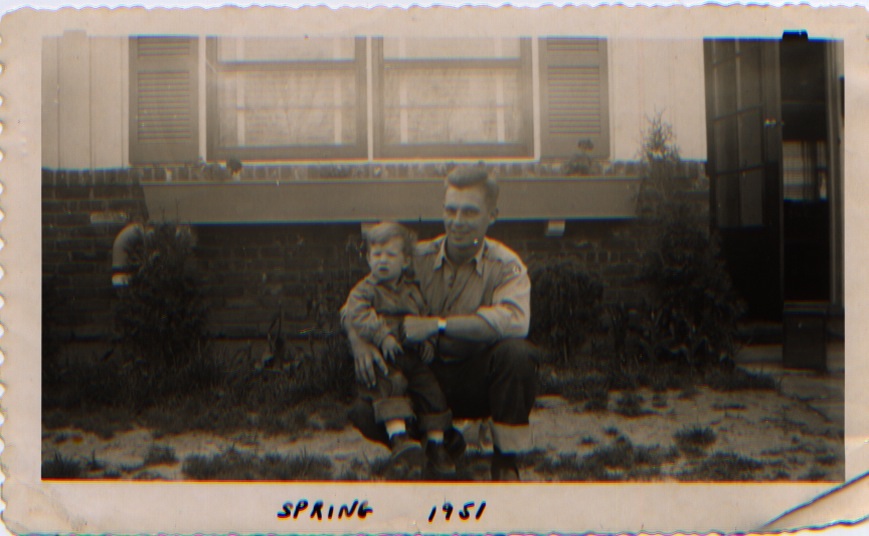

NOTE: I originally posted this back in August, 2008 — before I knew how to insert photos.

——–

I love baseball. It’s kind of ridiculous, I know. But it’s not like I had a choice.

As the youngest of seven children, I remember lying sprawled on the tiles of our playroom floor, the television turned to a ballgame, my mother moving from the washing machine to the dryer, bending, lifting, hauling, then over to the ironing board, then back, again and again.

At one point in her life, before I came along, before preschool was in vogue – this was the 1950s, deep in the post-war suburban dream – my mother had five children below the age of seven. It kept her busy. She was busy still in the 1960s, back when I was a pup.

So there she was, that white-haired mother of mine, rooting for her “Metsies.” I learned their names – Cleon Jones, Tom Terrific, Cool Koos and Eddie Kranepool. My mother, a good Irishwoman, showed a decided preference for Wayne “Red” Garrett, the young third baseman who was an average player on his best days, but handsome in that freckled, honest, Irish way. (It was only in later years, as baseball changed, when her crushes shifted to undersized Spanish-speaking shortstops like “little” Jose Oquendo and Raphael Santana.)

Before my mom went Latino, she always

favored the Irish boys.

I also learned the names of the players on the other side, those Mets-killers who broke our hearts. Their names were Shannon and Perez, Clemente and McCovey, Banks and Aaron.

Today I still repeat my mother’s line, inherited and ingrained, whenever a tough batter steps to the plate: “Uh-oh, he’s trouble.”

In my heart, my mother is linked to the New York Mets, and there are times when I don’t know if my love for one is a confusion for the other; or if, in my affection for the Mets, I am only expressing that childlike love I once carried – and still carry – for my mother, the soft lap I once rested my head upon, her hand in my hair. There she is at the end of the couch, a glass of crushed ice on the table, from which she constantly bites and chews. And the game is on the screen, the announcers’ voices in my ears. I am content, I am at home: the game is on and I’m with my mom.

She taught me how to catch, my mother, how to play. That wasn’t Dad’s department. Blithely indifferent, or just otherwise occupied, he didn’t care about sports. We never played catch, or hardly ever. That’s okay, because Mom did. And I liked Mom, plenty. She had a good arm and soft hands.

My mother taught me how to catch and throw.

But I crushed her at ping pong. No mercy.

I remember as a Little Leaguer asking, “Mom, am I graceful?”

She liked grace, my mother, the smoothness that certain outfielders had when they drifted back to the warning track, glove stretched out, eyes in the clouds, finally cradling that ball to the dull, soft slap of leather.

“Yes,” she’d answer. “Very graceful.”

And today, like her, like then, I still snap off the television in despair when the Mets play poorly. “I can’t watch anymore!” we’ll both exclaim across the years and miles, attached by an invisible thread.

Ten minutes later, both of us will again reach for the clicker, filled with the unquenchable hope that is at the heart of every game.

Now I can see that same sweet dynamic in my own children, particularly the two boys. They follow the game, just as they once obsessed over dinosaurs and super heroes, books and guitars. Now it’s baseball. All mixed up and confused with their love for me, I know.

After all, I should, I helped weave the blanket of baseball that wraps around us.

Sometimes I even hear them say it, when certain sluggers step to the plate, Chipper Jones perhaps, or the redoubtable Albert Pujols:

“Uh-oh, he’s trouble.”

By the late 60’s, my mother most feared

RBI-men Mike Shannon and Tony Perez.

But Mom would agree: this guy broke the hearts

of more Mets fans than any other player.