I’ve been doing a lot of school visits, book signings, and book fairs over the past two months. It’s been a lot of fun, distracting, joyful, happy, hard, and humbly rewarding. One of the highlights of my act — between juggling chain saws and wrestling live bears — has been reading Mighty Casey, illustrated by Matthew Cordell, to audiences up to 200 (squirming, wriggling) children. The book really goes over well (if I don’t say so myself), especially when I stop and go into great uproarious detail about Ronald the Runt, who has to pee, “and decided left field would do.” Kids love that part, and it’s absolutely true to my coaching experience. Happens every year. Some of those little boys just want to play and play until the lastpossiblesecond, not missing a thing, and they don’t always make it all the way to the bathroom.

When Ernest Thayer wrote the original “Casey at the Bat,” published in a San Francisco newspaper in 1880, he considered it a mere doggeral. He even used a pen name, to disassociate himself from the poem that would later (ironically) define his career.

I never really thought of Mighty Casey as a poem, per say. It rhymes and bounces along well enough, but it’s not, to me, poetry. Like most published books, it went through various drafts and revisions. And it was definitely made better through the help of my editor at Feiwel and Friends, Liz Szabla. As a rule, anybody with two z’s in their name has to be awesome. Name your child Buzzy and you are guaranteed a terrific kid. Anyway, here I am digressing once again, suggesting names for your children, which, let’s face it, is probably a personal decision and none of my business. But: Buzzy. Think about it.

I just came across an editorial letter from Liz, with comments and suggestions in response to the first draft of Casey (that is, the first draft that Liz saw; not the first draft I wrote). The way this works for Liz is like this: We’ll talk on the phone, go through things in a general manner, and she’ll follow that up with a more detailed “formal” letter. Most editors seem to work this way. Below you’ll find the bulk of that letter, with only a few passages removed to save the author from further embarrassment. I should also note, for those interested in the publishing process, that I didn’t see that first draft as a finished piece. It needed work and I knew that. But I had reached the point where I needed another eye, another point-of-view. I needed, that is, HELP! And Liz was there to catch me.

MIGHTY CASEY is mighty charming and we’ve enjoyed the time we’ve spent with it. I’m delighted now to be sending you our thoughts as well as a line-edited manuscript. You and I haven’t worked together before – please know that all my suggestions are open to further discussion if anything doesn’t feel quite right.

First and foremost, the Delmar Dogs are hilarious! Casey, as the unlikely hero, is wonderful. And the echoes of “Casey at the Bat” make Casey’s final triumph all the more satisfying, of course.

Let me break in here to comment that all editorial letters begin with a compliment. It’s a trick they teach you early on in Editorial School. The editor opens your ears by saying something positive. I tell this to kids who do peer writing in school: Always begin by saying something nice. Find a part in the story that you like and praise it. That way, you increase the chances of the writer hearing any critical suggestions you might later make. I’m saying: Liz didn’t fool me; I knew there was a big “but” in there somewhere.

You’ll see that I’ve make some suggestions and tweaks on the manuscript to fine-tune the rhythm or syntax in places. I won’t detail those suggestions here, but do let me know if I’ve fouled anywhere (heh, heh). Now onto a few issues to keep in mind as you consider the line-edit….

Note: the “line-edit” is the marked up manuscript, with more detailed comments and suggested changes in the dreaded red pencil. The general editorial letter comes along with a marked-up manuscript, which can be a cold thing, almost painful. Thus, the editorial letter serves as fabric softener to the line-edit’s starch. (Oh dear me, a laundry metaphor? Move on, people, there’s nothing to see here, nothing at all . . . .)

4th stanza

Although the “enjoyed…destroyed” rhyme is marvelous and unexpected, I can’t help but wonder if, in the fourth stanza, the parents’ feelings about the game are at odds with the Dogs’ pride at trying their best. To say that the adults don’t “enjoy” the games is a bit of a disconnect with the spirit of the Dogs. Still, I certainly see how it might be tough for the parents to see their kids trounced, and if this is what you intend, then let’s leave it. But if you want to work on another layer of subtlety – that is, the kids’ pride being stoked by their parents’ empathy, then I believe it’s worth exploring.

This is an example of an editor forcing the writer to think. I had to go back and look at what I was attempting to achieve in that stanza. I suspect Liz’s motherly instinct was to keep the parents cheerful and positive, whereas I wanted the recognition of how tough it can be to sit in those stands sometimes. In the end, I pretty much kept this stanza as is, but Liz made me to think about it and justify those words in my mind.

13th stanza

I’m a bit confused about why so few spectators notice or cheer when Jinn Lee bloops a double and later scores a run. Here’s where I see the Dogs and the parents on their feet, pumping their arms in the air!

Liz was right — and she was right in many places — so I changed it. The revision now reads: “When Jinn Lee clubbed a homer/The crowd stood and cheered.”

18th stanza

As Casey steps up to bat, there are a few things readers should know: How many outs are there? That is, is he the team’s last hope? If he strikes out, do they lose? If the situation is clarified, then you’ll really ratchet up the suspense in this last section.

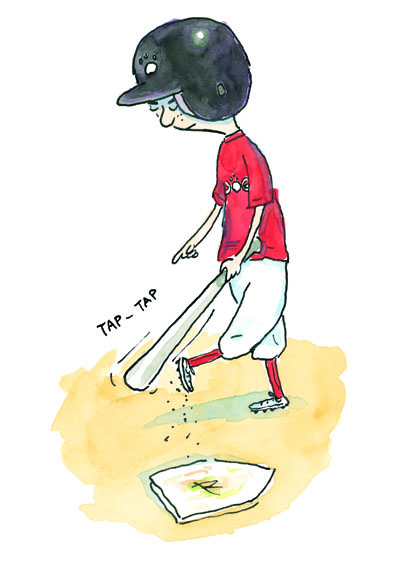

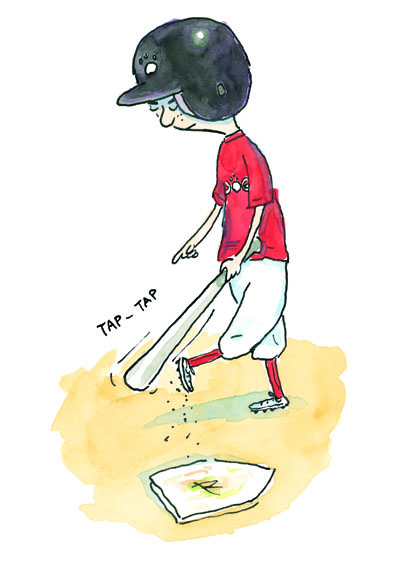

Again, just some essential details that I completely neglected to add. Or perhaps assumed. The facts were there, but I didn’t make them clear, clear, clear. This is a common kind of editorial suggestion — to “pause a beat” — forcing the writer to slow down, to really set the scene for the reader. Sometimes we’re in such a rush to get to the next thing, we don’t always properly build up to that Big Moment. It’s a Hitchcock trick. Once you’ve built up suspense, it’s time to slow things down. Think of those movie shots when we see close-ups of the killer climbing the steps, footfall by footfall. The doorknob slowly, slowly turns . . . or Casey taps his cleats.

The finale

I suspect the ending could have more zing to it…. The mother crying and the father’s heart bursting with pride seem stereotypical amid all the other fresh action and description. The fact that they’re stereotypical does fit the tone and conclusion of “Casey at the Bat,” but I believe descriptions that are as fresh as the rest of the story will complement the tone and mood you’ve established and make for a stronger ending. Also, the “bursts with pride” description echoes the language of the 3rd stanza (“bursting pride”). Would you consider echoing some of the language in the ending for “Casey at the Bat” instead? “[H]earts are light…men are laughing…little children shout…”?

The very last line is also in need of some zing. “Three cheers” feels predictable and “our side” seems too general and not exciting or punchy enough for a conclusion. Perhaps you can work “Delmar Dogs” into the final line, so that it appears in the opening and conclusion, just as “Mudville” does in “Casey at the Bat.” What do you think?

Hey, I knew the ending wasn’t right (to put it kindly). I probably even said so when I handed in that first draft to Liz. I was struggling with it. I remember interviewing James Marshall, tape recorder rolling, back in the early 90’s. He said something that always stuck in my head, simple and profound: “It’s always the ending that gives me the most trouble. The ending is what people remember. If the book fizzles in the end, they remember the whole thing as a fizzled book. It’s important to have a very satisfying ending for the reader. They’ve entered a world and now they are leaving it. So it’s a puzzle that has to be solved. I remember with one of the Miss Nelson books, it took us [the author Harry Allard and I] two years to come up with an ending we liked.”

Liz concluded her letter:

This is already so much fun – I believe that with some fine-tuning, it will be an even more dramatic and satisfying experience. Jean and I look forward to seeing what you come up with, Jimmy.

Please call or email me if you have any questions, or want to discuss any of these issues further.

Aren’t I fortunate to have such a warm, insightful, supportive editor? Liz made me think. She offered ideas and suggestions, but always made it clear that it was my book, my decisions. She got me to get back to work, keep hauling those rocks — but without feeling bad about myself, or my book. Instead I was energized, enthusiastic, ready to roll up my sleeves. Now you can see why so many authors dedicate books to their editors. We know we couldn’t have done it quite so well without a lot of help from the unseen hand of a talented editor.

Every time I read Mighty Casey out loud to a group of kids — when they laugh in the right parts, when they lean in to learn what happens next, when they burst into applause at the end — I always think of Liz and my publisher Jean Feiwel, and wish that they could be with me to share in the moment. The applause is also for them.