–

–

“Telling stories is a way to bond, to share

and connect emotionally,

even across great differences and divides

of time and space.

When I write, I am asking the reader

to really see something with me —

to share our imaginations.”

— Alexandria Giardino

–

I’m happy to say that I made a new friend recently. Yeah, true fact! It’s not always easy in these Covid times. Her name is Alexandria Giardino, and she’s the author of a new picture book, Tree + Me, gorgeously illustrated by Elena and Anna Balbusso. In a starred review of the book, Kirkus concluded, “Lovely—a perfect segue into discussions about loneliness, empathy, refugees, and more.” So I reached out to Alexandria because I was eager to talk about this book and learn more about its author. It turns out that we shared a lot in common — trees, dogs, nature, poetry, art, music — and found it remarkably easy to talk about our interests and passions. So, yeah, we’re pals now. Five bucks says you’ll like her, too.

–

You mentioned elsewhere that this book was, in part, a reaction to Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree.

This is definitely my reply to Silverstein’s work. I hadn’t read The Giving Tree since I was a child, and I had really fond memories of it. When I read the story to my son, I was completely conflicted. Old feelings of being touched by the bond between the boy and the tree were mixed up with new feelings of despair that the book’s true message is about taking, not about giving. Like, it could be called The Taking Boy.

But you did something refreshing, in that you brought it to a positive place.

I know there are important feminist readings of the story and also environmental ones. I wanted my own reply to be about mutual giving. To me, that is a basis for a true bond.

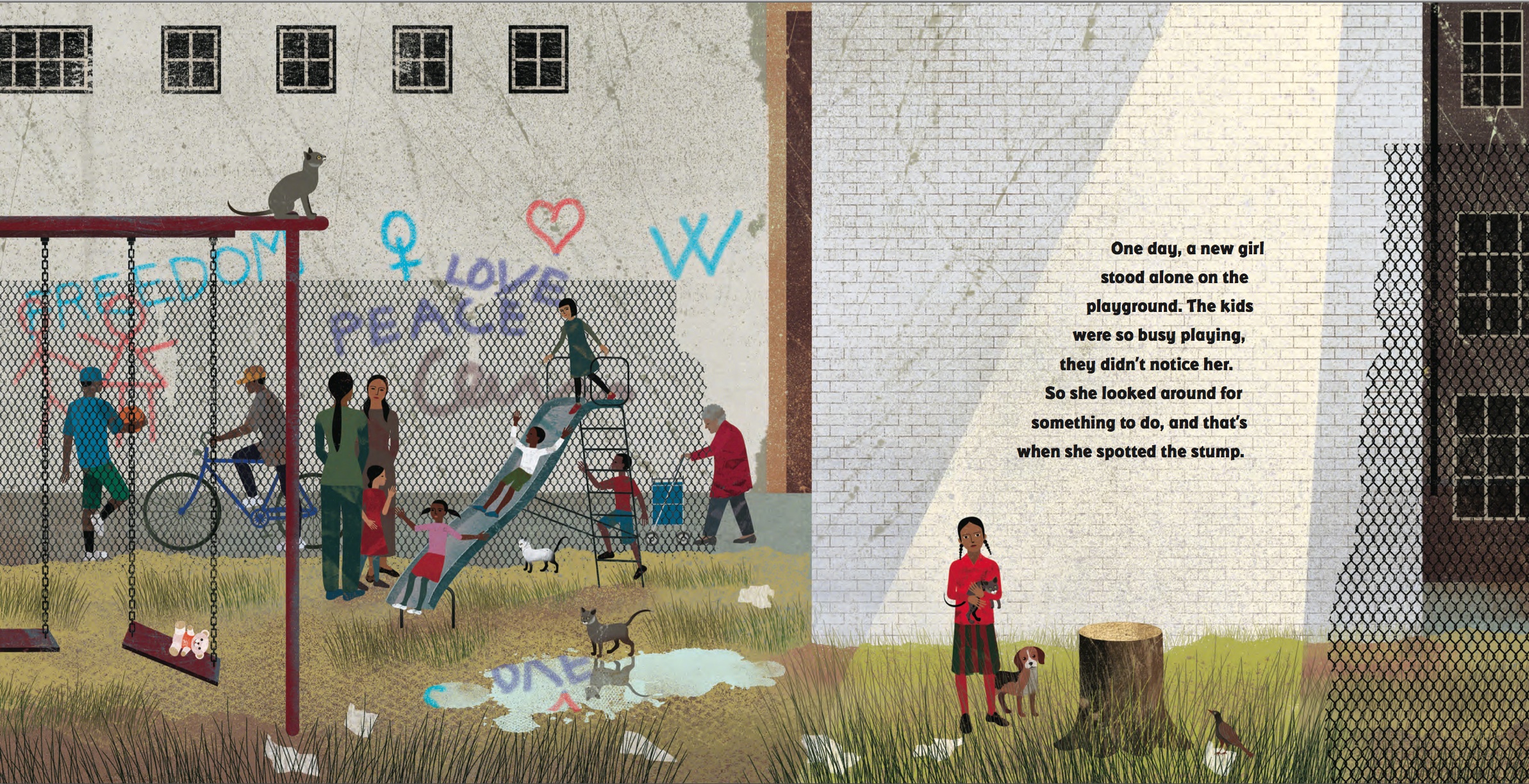

And so you got the idea that this lonely young girl would tell her story to the tree.

–

–

Telling stories is a way to bond, to share and connect emotionally, even across great differences and divides of time and space. When I write, I am asking the reader to really see something with me — to share our imaginations. I imagined a girl who was sensitive enough to know that a tree has a story to tell too, and that her story and its story might be deeply bonding.

I think talking to trees is a good thing to do, anyway.

I confess that I’ve always loved trees, too. It’s probably what drew me to your book. Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate, was a powerful, illuminating text  that explored the science behind tree-to-tree communication. And in fantasy literature, we have a great tradition of “magical” trees — Tolkien’s Treebeard at Isengard! — and so on. It’s nice to see those notions supported by hard science.

that explored the science behind tree-to-tree communication. And in fantasy literature, we have a great tradition of “magical” trees — Tolkien’s Treebeard at Isengard! — and so on. It’s nice to see those notions supported by hard science.

Science is always challenging the word fantasy. Like, what once seemed fantastical is actually quite explicable! Oh, science, I love you. I admire Wohlleben’s book, and I still need to read The Overstory.

Yes! The Overstory was one of my favorite books of the past decade. Loved it.

This year there are four other tree-related picture books coming out, and I reached out to those authors/ illustrators, saying, hey, let’s be forest friends. And being awesome and generous kidlit people, they said, yes, let’s! So we have some fun things brewing to share our love of trees, including a bundled give-away for teachers and librarians that we are doing in March-April. Stay tuned for that.

While looking at your website, it strikes me that the act of “a creative response” is important to you. Your book Ode to an Onion was inspired by one of Pablo Neruda’s poems. And on March 13, you are presenting an online craft workshop, “Countering the Classics,” encouraging participants to seek way to counter classics by using their own voices. It becomes a living, and inclusive, conversation.

–

–

I love talking. Some of my happiest memories are times when I took a long walk with someone, and we got into a deep talk. So, that passion is definitely part of my creative life. I also believe we have every right to claim a literary heritage and have conversations in it, with our ancestors and our descendants too. Neruda is part of my heritage, and so is Silverstein. Who ever thought they’d be in the same family tree?

For a picture book writer, there’s always that –- gulp – moment when the art comes in. I guess that was a good day?

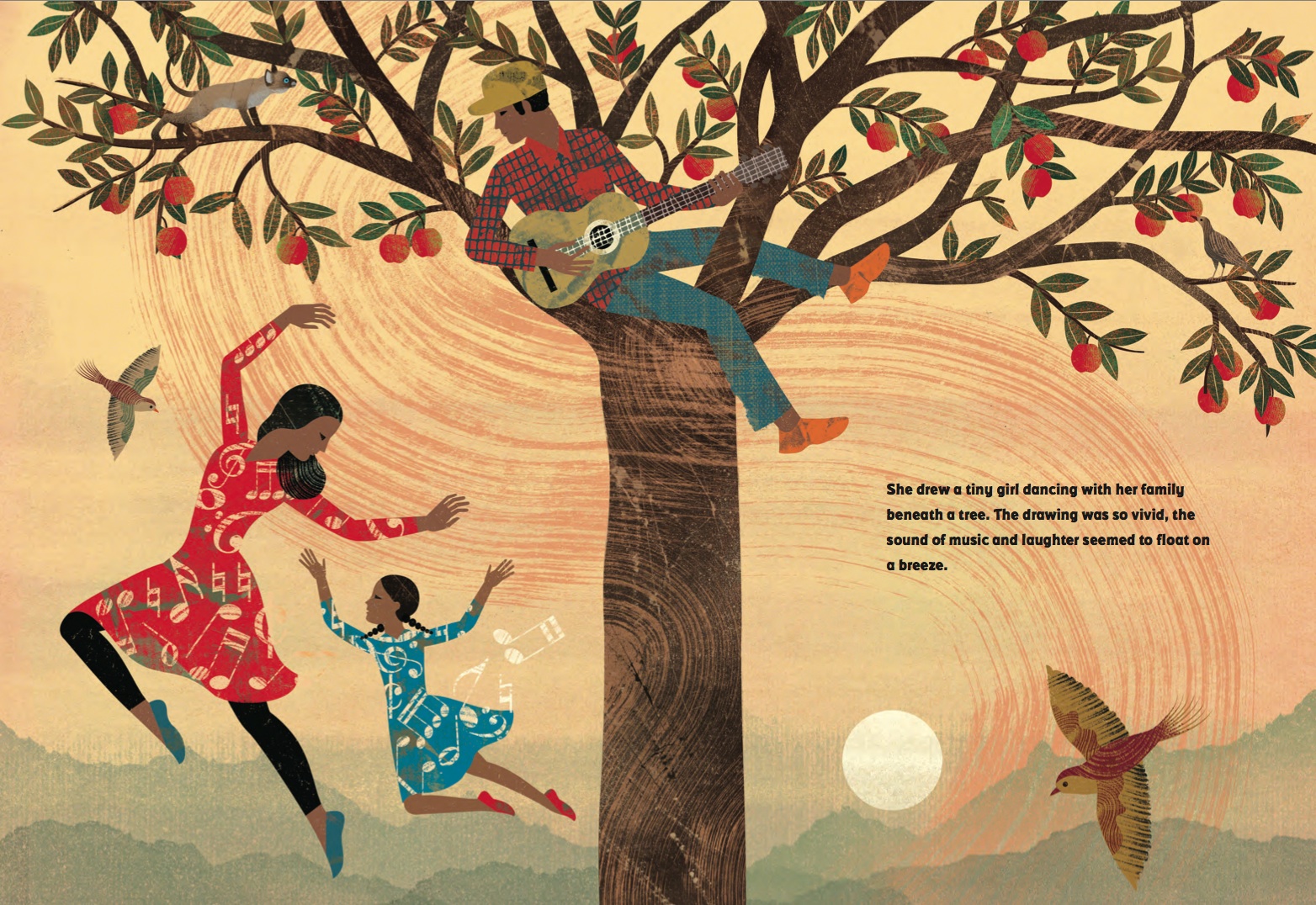

Ok, so there is a twist to my “gulp” moment because it is not as simple as seeing artwork and being happily surprised, or possibly disappointed. When I saw the early artwork that the Balbusso sisters sent in, I was shocked. I felt like they “saw” something in me, or sensed something about me, that led them to create art that just truly blew me away.

Specifically, what I mean is that I am a major Santana fan. And their earliest drawings looked like the Abraxas album cover. Even the book’s opening page — with the colorful tree rings — looks like a vinyl record. And the palette they chose had a very late Sixties vibe. My editor, who does know how much I love Santana, called me and said, “Alex, you are NOT going to believe your eyes when you see this artwork.”

Honestly, that gulp moment was like, well, we are in tune.

The art is stunning. And mind-blowing in that they are not only sisters, but twins. Talk about communication! Those two must have some serious telepathy going.

I’m a deep believer in some abilities that we can’t yet fully understand yet. But, you know, science will eventually show us. Also, I so look forward to the day I can meet them. I bet they are fascinating women. We’ve been emailing back and forth, dreaming of the day when I get to Milan, so we can go out for a meal together.

–

–

Is there anything of you in our heroine’s story?

Loneliness and longing for deep connection and true friendship. I have lived in a lot of different places, and I have often been an outsider, even unable to speak the local language. I have often taken refuge in nature because of that. I would have totally talked to a tree stump as a lonely kid.

I love that crucial moment when she whispers, “I see you.” To be honest, I have a similar moment, in a very different context, in my upcoming novel, Upstander. A mother says it to her daughter. Honestly, I think that’s all anyone really wants. Just to be recognized, seen, valued.

Thank you for telling me about your book. As I mentioned earlier, I think most of us long for that deep sense of being understood and loved. That is, to be seen. That actual line came late in revisions. But where this story started in my imagination is with the image of the final moment. I always saw the sprout breaking through. I felt that moment in my heart.

Actually, that is how I seem to write. I am one of those writers who sees the last scene first, and then has to write back from it to the beginning — that green shoot at the end of the book is everything. It is life coming back after such loss and despair.

Actually, that is how I seem to write. I am one of those writers who sees the last scene first, and then has to write back from it to the beginning — that green shoot at the end of the book is everything. It is life coming back after such loss and despair.

I’d love to learn a little more about you, Alexandria. Where did you grow up?

As a kid, I moved around a lot, but my heart belongs to my first home, Oakland. As an adult, I continued to move quite a bit, including living for a long time in Mexico and Chile, and even a little time in Italy.

How did you come to children’s books?

I wrote my very first children’s books while living in Mexico City in the late 1990s. I am so glad I found my way to picture books because I love the marriage of story and art so much. And now I am also writing verse novels. I feel I have found my even truer voice there.

I wrote my very first children’s books while living in Mexico City in the late 1990s. I am so glad I found my way to picture books because I love the marriage of story and art so much. And now I am also writing verse novels. I feel I have found my even truer voice there.

Can you tell us more about that verse-novel project?

Oh yes! I am having the most profound experience writing this new novel. I have always felt like a poet, but I was just too shy to say so. This story is pouring out in verse, so I am going with it. It’s supernatural historical fiction, based on a woman whose story has never been fairly told. She deserves better.

Lastly, you are a “major” Santana fan. Does that mean you have Carlos Santana’s head tattooed on your back?

I saw him once live. I was able to get right up to the stage. He expressed so many emotions! At one point, he turned away from the crowd, lost in the music, channeling something divine. Now, I have tickets to see him in a  concert with Earth Wind & Fire. The show was scheduled for last June, then COVID hit, and now it is rescheduled for some future date. I can think of no better place to be with people outdoors again, dancing while Santana and Earth Wind & Fire play. Please, lord, let that concert happen one day.

concert with Earth Wind & Fire. The show was scheduled for last June, then COVID hit, and now it is rescheduled for some future date. I can think of no better place to be with people outdoors again, dancing while Santana and Earth Wind & Fire play. Please, lord, let that concert happen one day.

Thank you, Alex, we share many interests. I feel like we could talk for days. Before we go back to the real world, should I cue up “Soul Sacrifice” — or do you have a different suggestion?

Ah, I love that song. But you know which one is really great too? “The Calling.” I get chills. The guitar talks straight from his heart. Thank you for this conversation. I feel so grateful for the ways we have connected here and for your willingness to connect.

Alexandria keeps up a clean, neat, tidy, informative website.

Alexandria keeps up a clean, neat, tidy, informative website.

Also, you can learn more about her by using this amazing resource called Google.

As for me, James Preller, I’m the author of the Jigsaw Jones mystery series. Coming this Spring, look for my new middle-grade novel, Upstander, which is a stand alone, prequel/sequel to Bystander. Both are Junior Library Guild Selections (along with Blood Mountain, below). Thanks for stopping by. Onward and upward with the ARTS!

–

–