I want to tell a quick story about doing research. Specifically about Crayola crayons and the book, Along Came Spider. But first, a little back story:

As I was writing Spider, I did a lot of research in different directions. As I began circling this character of Trey Cooper, trying to figure out who he was, I wanted to show in his personality a number of traits that were consistent with children “on the Spectrum,” as they say.

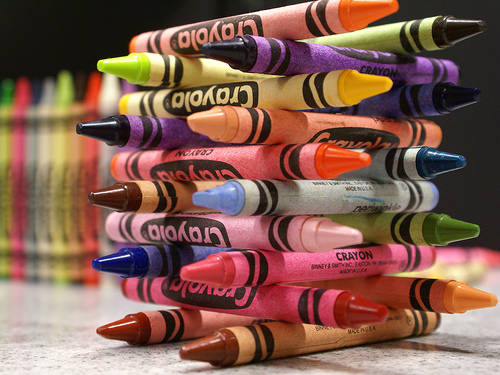

Trey has difficulty reading social cues, struggles during transitions, and generally comes off to his classmates as a quirky, even weird, kid. I also wanted to show Trey’s many strengths and outstanding qualities. He’s an expert on birds, for example, and builds wonderful bird houses. One of his talents is an interest in art and coloring. He loves his huge set of Crayola crayons.

In order to write about that, I did some quick research on Crayola. Specifically, I was looking for the names of their crayons. Well, one click led to another and I found this factoid:

1962: Partly in response to the civil rights movement, Crayola decides to change the name of the “flesh” crayon to “peach.” Renaming this crayon was a way of recognizing that skin comes in a variety of shades.

Wow, I thought, and immediately knew it would have to find its way into the book. Just a little nugget, a gem I came across while looking for something else. And I think that’s the core of research, trying to stay open to what you might find, casting a wide net, and recognizing the gems along the way. Sometimes what you (think you) want isn’t what you need.

What would Trey think of a crayon called Flesh? Would he know, or care? (He hates the name Fuzzy Wuzzy Brown, which was added in 1998 — way too babyish.)

I’ll sometimes talk about all this on school visits. I’ll say something like, “When doing my research, I learned that Crayola used to have a color named Flesh. But they changed that name in 1962. Would anyone like to guess why?”

The answers are often surprising. And maybe a little disappointing. One boy speculated that it was too disgusting — flesh, yuck, gross me out the door. But sooner or later, with or without a hint, somebody figures it out. We’ll talk about it briefly and move on. But hopefully it gets these kids to think a little, about research, about differences, our assumptions and our attitudes.