–

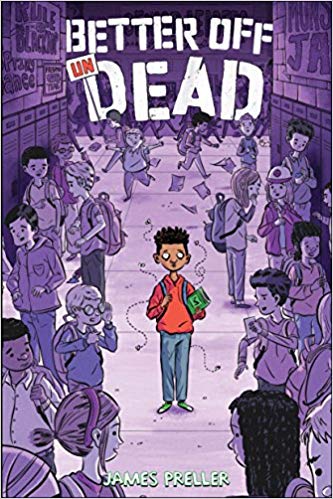

I met a middle-school librarian recently who loved this 2017 “cli-fi” book — she thought it was my best book — and it prompted me to take another look at it.

And guess what? She’s right!

Ha, ho, heh.

Though this book received excellent reviews (and a star from Booklist), the sales never quite got there. A disappointment. And somehow, sadly, no matter how I initially felt about the book, it slowly became tinged in my mind with that stigma. A disappointment. Not good enough.

Though this book received excellent reviews (and a star from Booklist), the sales never quite got there. A disappointment. And somehow, sadly, no matter how I initially felt about the book, it slowly became tinged in my mind with that stigma. A disappointment. Not good enough.

So it was wonderful to fall in love with it all over again. Or to at least nod and think, Hey, not bad. To know that it’s good, and funny, and mysterious, and smart.

Here’s an excerpt from the middle of the book, a point when the plot begins to thicken nicely. Adrian is a 7th-grade zombie; Talal is a classmate and a detective; Gia is a new girl with purple hair who seems to be able to see into the future. And that’s where this book is set, btw, the “not-so-distant” future. A book that references pandemics and face masks and super flus and water wars and climate change and a pair of evil corporate billionaires not too unlike the Koch brothers.

Here, take a swig . . .

—

Talal Clues Me In

–

I was still asleep when Dane knocked on my bedroom door.

Key word: was.

Past tense.

“Go away,” I grumbled.

“Your friend is here,” Dane called through the door.

I looked at my clock. It was 8:15 on a Saturday. I sat up, holding my head in my hands. It felt heavy, like a large pumpkin. “Who is it?”

Dane poked his nose into the room. “I don’t know. I never saw him before. He’s wearing a raincoat. And, um, he’s carrying two umbrellas.”

Umbrellas? The sun’s hazy glare streamed through my window. The sky was crisp blue, like an ironed shirt. For a moment, my mind still sputtering, I thought it could have been Zander. Then I remembered the coat. “His name is Talal,” I told Dane. “Tell him I’ll be right down.”

“In your boxers?” Dane asked.

“Just go,” I said.

When I arrived downstairs, I found Dane sprawled on the floor, working on an “Endangered Species” puzzle. Pieces were scattered everywhere. I asked, “Where is he?”

Dane pointed to the side door.

“You didn’t invite him in?”

“He wanted to wait outside,” Dane replied.

I went to the sink to swallow down a large glass of water. Still working on hydration, you know. Out the kitchen window I spied Talal standing near our big, sad rhododendron, its leaves turned yellow and brown. Although it was a picture-perfect morning, Talal held a large, black umbrella over his head. “I won’t be long,” I told Dane.

“Can I come?” he asked.

“Sorry, bud. Next time.”

Outside, I squinted in the sunlight. I said. “You woke me up, Tal. Come on inside while I make a shake.”

“I’d rather not do that,” Talal said. “The walls have ears and eyes. Here,” he opened an umbrella and handed it to me, “hold this.”

“Dude?”

“I’m serious,” Talal said.

I studied his face. He wasn’t joking.

“Let’s walk,” he said. ““It’s about that drone. Leave your phone.”

“My phone? I need it,” I said.

Talal shook his head. “No phone.”

“Okay, okay,” I said. I placed my cell on the patio table.

Talal walked toward the back gate. I caught up with him. Both of us an absurd sight, carrying open umbrellas on a sunny day.

“Do you know they can activate all the cameras that are inside our computers?” Talal asked. “You have a smart kitchen, right? Everything’s run by computers. We don’t have to remember to turn off the lights anymore. Cars drive themselves. Our machines automatically order kitty litter when we run low. Think about your phone. That spectacular piece of technology can record every word you say. It can locate exactly where you are. It knows what you ate for dinner and how many hours you sleep. Don’t you understand? They see what you see.”

“Whoa, ease up,” I said. “Who are they?”

We walked along the street, close to the curb, not on the sidewalk. The roads were quiet. We had the sleepy town to ourselves.

Talal stopped. He pulled out a tiny computer chip sealed in a plastic bag. “I took that drone apart piece by piece,” he said. “I talked to some people, geeks I trust who specialize in this kind of thing. We know who is spying on you.”

I didn’t know what to say. It was all kind of unreal.

“There’s a tiny logo printed on this chip, invisible to the human eye,” Talal said. “But when put under a microscope magnified by the order of ten thousand, it’s as clear as day.”

He pulled a folded paper from his pocket. It was a print-out of an enlarged image. The K & K logo.

“So,” I said.

“So?” Talal echoed. “This proves that the Bork brothers are interested in you. They own the richest, most powerful corporation on the planet. They practically run the country. Those guys live in a compound only forty-five miles away, up beyond a crest in the Catskills.”

“Oh, right,” I said, remembering. “I think I heard about them, maybe.”

“They don’t like the spotlight,” Talal explained. “They operate in the shadows. But they are very powerful –- real financial wizards, and ridiculously rich. They are the ones who sent the drone.” He glanced around, eyes scanning restlessly. “They are probably trying to listen to this conversation right now.”

“That’s why you brought the umbrellas,” I said.

“Lip readers,” Talal said. “Their staff could videotape us without sound, then figure it out later. These guys will do anything to get the information they want.”

“What information?” I protested. “I mean, even if what you say is true –- that those Bork brothers are following me for some reason –- I don’t know anything! I’m just a kid. An average, run of the mill –-“

“—- zombie,” Talal interrupted. “Nothing average about you.”

I felt like he punched me in the gut.

“Sorry, but that’s the deal,” Talal said. “As far as I know, you might be the only person who has died, and yet still lives. That makes you different. And maybe it makes you interesting.”

We turned down a block, then another. “Can we sit?” I suggested. “My ankle.”

“Sure,” Talal said. He led us to a stone bench in the back of a nearby churchyard. He pulled a sheaf of papers out of his deep coat pocket. “I put this packet together last night. Sorry it’s sloppy. I didn’t have much time.”

The pages were neatly folded and stapled along the left edge. There was nothing haphazard about the way Talal worked. The top page featured a black-and-white photograph of infant twins, swaddled under blankets, in a hospital setting. The twins are turned toward each other as if whispering a secret.

Beneath the photo, a caption read: THE ONLY CHILDHOOD PHOTOGRAPH OF WALL STREET WIZARDS KALVIN AND KRISTOFF BORK.

I flipped the page.

The next photo was of the twins again. But this time they were aged men, heads close together, unsmiling, staring directly out at the camera. Once again, a large blanket covered their bodies from their necks down. At their knees, four identical legs poked out, wearing matching black socks and leather shoes.

“They look . . .”

Talal turned to me. “They look . . . what?”

“I don’t know. Just weird, I guess.”

Talal nodded, not saying anything.

I flipped through the rest of the pages. They were filled with numbers, charts, and newspaper clippings.

“What do we do now?” I asked.

“Nothing, yet,” Talal said. “At least nothing right now. Let me see what I can dig up on these guys. In the meantime, get used to sometimes going without a cell phone. Let’s not make it any easier for their people to spy on you.”

We headed back to my house. I had to check on Dane, he’d be worried. Talal stopped two blocks away. “We’ll part here,” he said. “I have a family thing.”

“Sure,” I said. “And, um . . . thanks, Tal.”

Maybe he saw something in my face. He said, “Hey, Adrian. It’ll be okay.”

“Sure, sure,” I repeated. And after a pause, I said, “You know, sometimes I have this crazy thought, but I’ve never told anyone.”

Talal just watched me, unmoving, waiting.

I gestured to the trees and houses. “I sometimes wonder if all of this is just a giant sim game run by a computer program for the amusement of super-beings. Do you ever think that?”

Talal actually laughed. “All the time,” he replied with a grin.

I limped home, my stomach oddly rumbling. Looking up, I noticed a wake of red-headed turkey vultures, at least twenty of them circling in a vortex high above me, holding steady without flapping their wings. I’d never seen that many at once before. They spiraled hypnotically round and round, riding pockets of warm air. Maybe they saw me with their keen eyes and sense of smell. Perhaps they were as puzzled by it all as I was.

I didn’t have an answer for them.

“Sorry, birds,” I murmured. “I haven’t got a clue.”

Dane was taking a bath when I got home. My mother was on the computer. I snapped on the television. A commercial came on. I’d probably seen it a hundred times before, but this time I noticed the names at the end of it.

The commercial flashed a series of short film clips, each more beautiful than the next. A fishing boat leaves a harbor, a man in a business suit gets into a cab, a rugged farmer drives a big-wheeled tractor, a cowboy saddles up, a car and moving van pull into huge home, a tear-stained grandmother watches a wedding scene in church, various citizens hoist American flags up flagpoles, rows of smiling children look up in wonder, a proud eagle soars across the sky. Final image: Logo on the side of a huge, glass-sided building for K & K Brothers Corp.

While all those images floated past, a man’s voice spoke in soothing tones. The words, as he spoke them, scrolled across the screen in block letters. They read:

BE AT PEACE.

THERE IS NOTHING TO WORRY ABOUT.

ALL IS GOOD, ALL IS WELL.

THE BIRDS ARE SINGING.

IT IS MORNING IN AMERICA.

BE HAPPY. RELAX. SMILE.

WE ONLY CARE

ABOUT YOUR HAPPINESS.

In smaller print, it read: “This has been a paid advertisement by K & K Brothers Corp.”

“That’s some frown, Adrian,” my mother said. She had joined me in the kitchen and was poking around in the refrigerator. “What’s bothering you?”

“Huh? What?” I replied. “No, nothing, I’m fine. I was watching that commercial and –-“

“Don’t you love it?” my mother said, while slicing into a giant-sized, perfectly pink, wonderfully round, genetically-engineered grapefruit. “I see that commercial every day, and every day it makes me smile.”

I made an effort to smile right along with her.

“Be happy. Relax. Smile,” my mother repeated. “Those are words to live by!”

I didn’t answer. Instead, I wondered why K & K Corporation was spending millions of dollars on commercials to brainwash us all.

They didn’t want us to worry.

Because of course they didn’t.

Everything was fine.

Be happy. Relax. Smile.

I went up to room and sprawled across the bed. I felt a strong urge to find Gia. She had an eerie knack of knowing what was about to happen. It was time we had a talk. My cell dinged. It was a message waiting from Gia:

7:30 tonight. Lookout Hill. Go to the bench that faces the tracks. We need to talk.

Once again, she was two moves ahead of me.

—

REVIEWS!

“This uproarious middle grade call to action has considerable kid appeal and a timely message. A strong addition to school and public library collections.” — School Library Journal.

Preller stylishly delivers a supernatural tale of a middle-schooler who craves normalcy, and environmental issues with some currency make the story even more relatable. Espionage, mystery, and the undead make for a satisfying experience for readers, and they’ll be glad of the hint at a follow-up. — Bulletin for the Center of Children’s Books.

“Preller takes the physical and emotional awkwardness of middle school to grisly levels . . . [and] thoughtfully chronicles the anxieties of middle school, using a blend of comedy and horror, to send a message of empowerment and acceptance.” — Publishers Weekly.

–

–