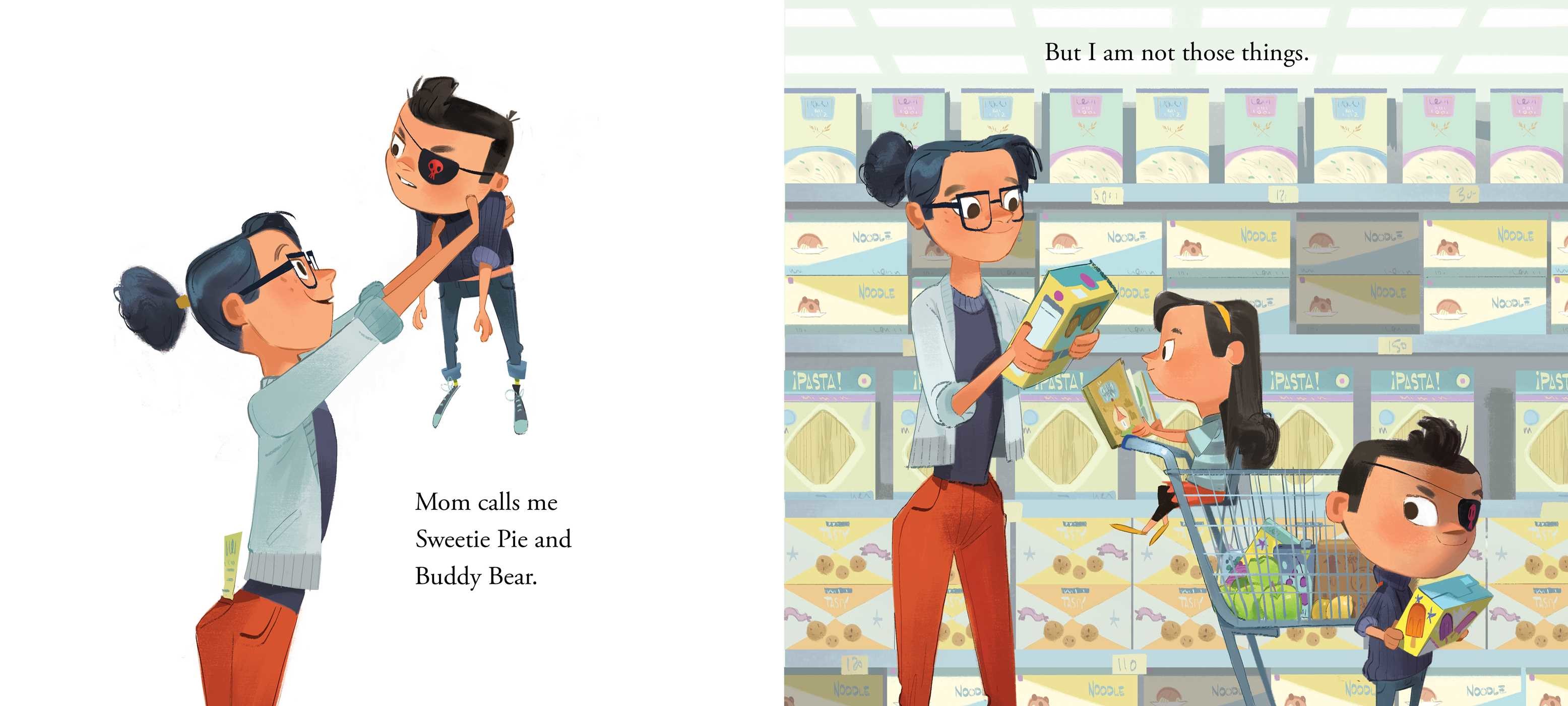

I think Hannah Barnaby can write anything. I first read her remarkable young adult debut, Wonder Show, and Hannah then followed that up with Some of the Parts. But now she’s pivoted with the bang-bang publication of two new picture books. Today we’ll focus on Bad Guy, illustrated by Mike Yamada. You’ll like Hannah. She’s thoughtful, perceptive, articulate and inspiring — even if I kind of hate her. What can I say? Jealousy is an ugly thing. I’ll try to be a better person next week.

–

–

Hey, Hannah. Thanks for coming by. I immediately noticed that your new book, Bad Guy, is a lot shorter than your previous works. And it comes with pictures. What’s going on?

Well, the thing about novels is that they take so long to read, and I know people are busy these days, and . . .

Actually, the truth is slightly more self-serving that that. While my second novel (Some of the Parts) was out with my editor, I went on a writing retreat. I knew I was supposed to be working on whatever novel would come next, but I had all of these picture book ideas jotted down in my notebook and in a fit of rebellion (or possibly laziness), I decided to work on a few of those instead. It was such a relief to think about story structure on that smaller, more concentrated scale! By the end of the retreat, I had three different stories that were in good enough shape to send to my agent. One was Bad Guy, another was Garcia & Colette Go Exploring (which comes out on June 6th). And the third . . . never sold. But two out of three ain’t bad!

Two out of three is fabulous. I think I’m 0-17 this year with a sac fly. When you write a picture book, do you page it out?

Not at first. I like my first drafts to be more open than that, so I can take few wrong turns and get a little messy. That’s usually how I find the less predictable path. But once I have a draft that works, I will often storyboard it to make sure that the pacing is steady and that I haven’t gone on too long with one particular part of the story. I think of picture books like stand-up routines—they have to be well-balanced and very structured, you have to leave room for the audience to laugh, and you have to know when to get off the stage.

Stand-up routines, huh? I think of my attempts at picture books as tragedies. There’s a lot of sobbing and snapped pencils. Anyway, did you interact with the illustrator, Mike Yamada? Or do you include art suggestions in your manuscript?

Mike and I didn’t have any direct contact at all. People are often surprised to hear that—I think they like to picture authors and illustrators having coffee together, collaborating like Lennon and McCartney. But it’s pretty typical for all of the work and communication to go through the editor and the art director, and that’s a good thing. It protects the illustrator from being penned in by the author’s vision of the story, and allows him or her to construct the visual narrative without being unduly influenced. That’s where the magic is in picture books, for me: that alchemy between words and pictures that are created independently and produce an entirely new experience.

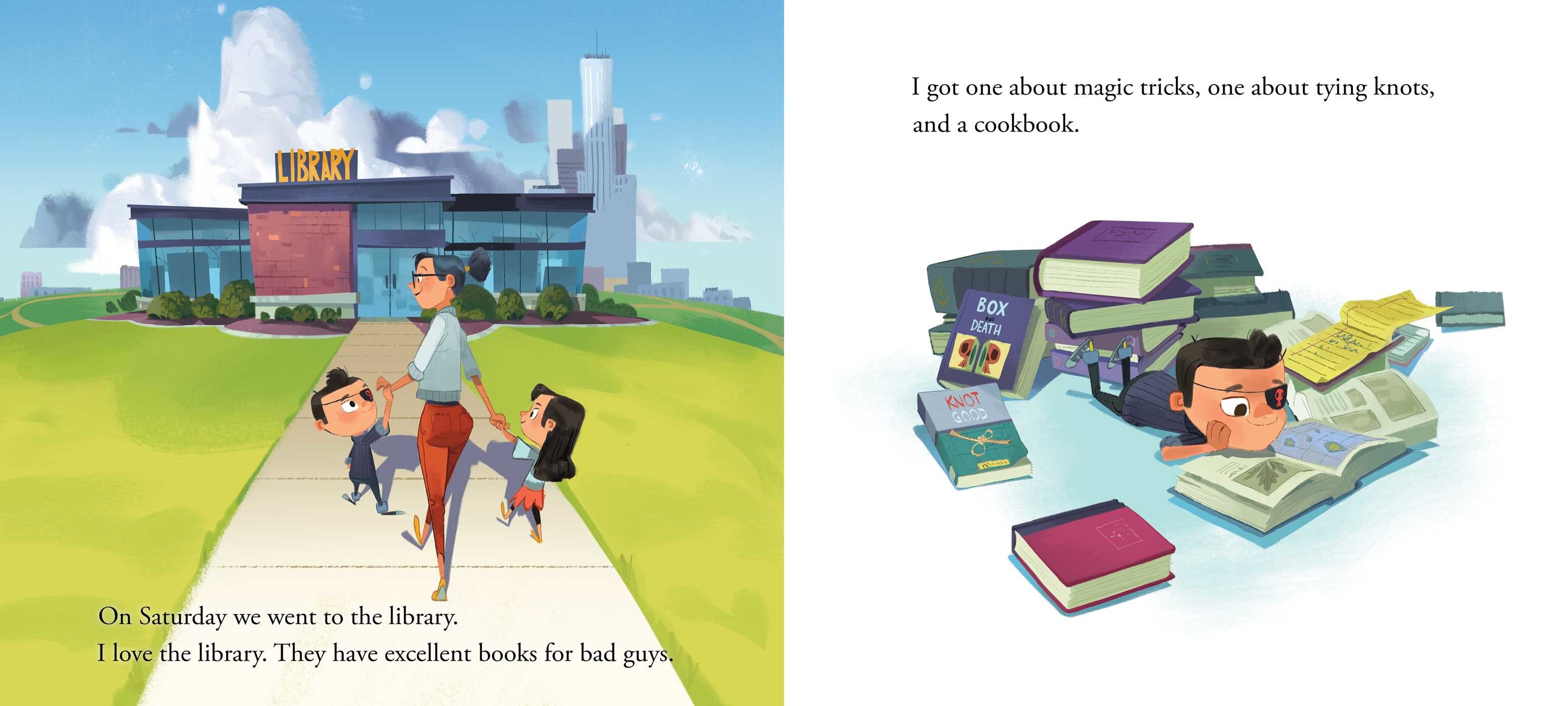

I did include a few illustration notes in the manuscript, but only so that Mike would be clued into the staging or the jokes that weren’t spelled out in the text. When Bad Guy describes his library books, for instance, and then says, “I had big plans,” I wanted to make sure it was clear what I meant.

Did your manuscript change a lot from earlier versions?

Looking back at earlier versions of the manuscript, you’d see that the text barely changed at all from submission to publication—maybe because it’s so spare (only 215 words), there weren’t a lot of editorial changes along the way. Well, except for one. Originally, Bad Guy’s woodworking project was a guillotine. My editor, Christian Trimmer, has a great sense of humor, but at some point he said, “There’s some concern around the office that a guillotine might be . . . too much.” I pointed out that Pepito builds a guillotine in Ludwig Bemelmans’ Madeline and the Bad Hat, but it was a non-starter. So we changed the woodworking book to a magic book, and Bad Guy builds a box to saw his sister in half instead. Still pretty edgy. But not as sharp.

So the art finally comes in and you did . . . what?

Squealed, jumped up and down, et cetera. Art delivery days were always my favorite part of working as an editor at Houghton Mifflin—we would spread everything out on the conference table and walk around it, oohing and aahing. So I did that in my kitchen. And I made my kids do that, too.

There were a few rounds of email and a phone call or two with my editor, between sketches and finished art, to make sure all the details were right and to cut out a few extraneous words. Paring down a picture book text any further always seems impossible, but once the illustrations are in place, there are almost always a few spots where the editorial scalpel can be applied.

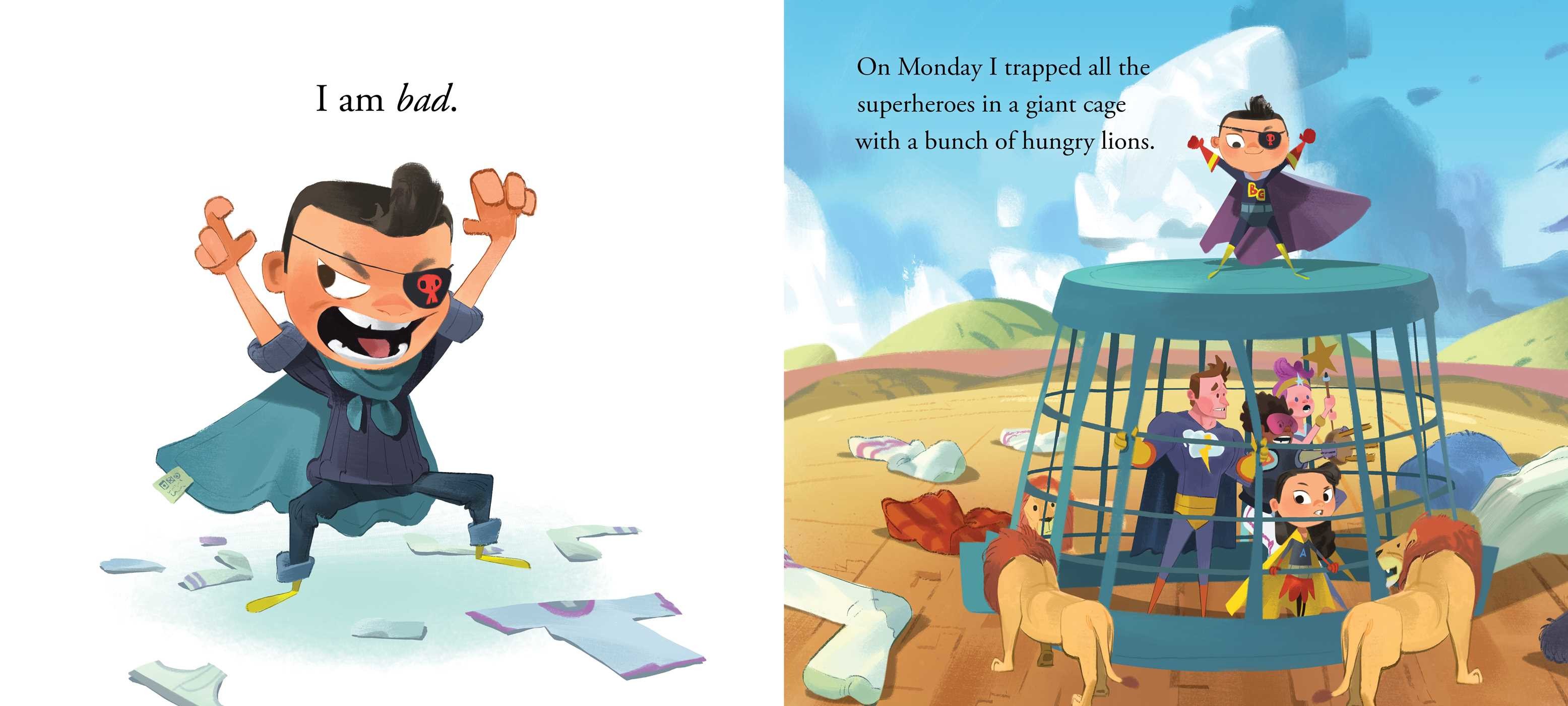

People have always been fascinated with “bad guys” – and these days with shows like “Breaking Bad” and “The Sopranos,” we’ve even come to root for the bad guys. They are our favorite characters. Why do we like bad guys so much?

Because they’re complicated. Because they get to do things we never would. Because they break rules and embrace their id and make things interesting. Ever since Milton wrote Paradise Lost, the devil’s been the character that throws complications and color and energy into the story. But the trick is making sure your villain is complex—just as every superhero has a vice, every bad guy must have something they love. Even something as simple as orange Popsicles.

This book turns on a joke -– spoiler alert: a gender assumption –- was that element there from the beginning?

The twist was always there, but it took me a while to figure out the phrasing. Because the story has so few words, I knew that whatever the “punchline” was going to be, it would have to be snappy. What I’ve loved most about sharing the book with groups of kids is their reaction to that moment—when I first hold up the book, all the boys hoot and holler, but when I read that final bit of text, the girls go wild.

So you knew how it would end?

I did. I never want to moralize in my books, but I’m very aware of the responsibility of writing for kids and the power of stories to shape their worldview. So even though I set out to portray this little boy who fully embraces playing the villain, I knew all along that he would have to face the consequences. And I wanted them to come from Alice, his sister, rather than from his mother (who is up to a few tricks of her own).

I’m usually good with writing the first 2-3 pages of a picture book, the opening. But the middle, oh boy. That’s rough. What was hardest for you?

Oh, middles are the worst. Beginnings are fun and endings are thrilling, but middles . . .

The good news is that most picture books are built on reliable structures, with reliable patterns. I have done classroom workshops on story-building and it’s amazing how many different scenarios you can construct out of a character or two, a problem, and three (increasing) attempts at a solution. Once you get comfortable with that formula, you can mess around with it a little and twist it in different directions to get that unexpected angle editors are so often looking for.

Could you expand on that? I mean, the formula part. And I wonder: Did you take creative writing in college?

Sure—so, most picture books that tell a real story (versus the “character portrait” books like Olivia and the conceptual/emotional books like Goodnight Moon and Love You Forever) are built on a pretty simple structural progression: a character has a problem and attempts to solve it in a series of escalating actions. The first try doesn’t work but informs the second; the second doesn’t work but informs the third; and the third does work, though perhaps not in the way the character intended. Along the way, the character grows and develops through these efforts, and maybe there are some other characters who help or hinder, and it helps a lot if there’s something funny like a banana or a sloth.

Or a sloth eating a banana! (Just brainstorming here, Hannah. Please continue.)

I only did one semester of creative writing in college, and it was an independent study with a children’s literature professor who also happened to be a picture book author. He was a storyteller, really, and working with him allowed me to dip a toe into the writing pool but still take an academic approach, which kept me in my comfort zone. (What I wrote was a pretty terrible first draft of a middle-grade novel about a boy whose voice is stolen by a witch. A silent main character is . . . not the best.)

Ha, yes, wrote yourself into a corner with that one. So what else is in the works? And try, Hannah, while answering this, to not make the rest of us feel too much like slugs on a couch. We feel bad enough about ourselves already.

Well, my second picture book—Garcia & Colette Go Exploring, illustrated by Andrew Joyner—releases on June 6th from Putnam. Two picture books coming out within a month of each other was a total fluke. I swear.

The tricky thing about this publishing business is that there are always things in the works that we’re not allowed to talk about, right? But I can say that I have a third picture book under contract with Houghton Mifflin—it’s called There’s Something About Sam, and it’s the story of a boy named Max who is convinced that there’s something odd about the new kid at school. (And he is right!) That will be illustrated by Anne Wilsdorf and published in 2019.

Novel-wise, I have shifted my focus from YA to middle grade and I have plans to work on a new manuscript this summer. For the record, this is a story that I’ve drafted twice before, but I still haven’t found the right path into the project. I have faith that it will reveal itself, but I also know the importance of showing up for the work. I invoke the spirit of Jane Yolen, who says, “BIC. Butt in chair. There is no other single thing that will help you more to become a writer.”

Jane is so right about that. And what I like about that famous bit of advice is the demystification of the process. For example, on school visits kids often ask about “writer’s block.” I tell them that my father was an insurance man from Long Island with seven children. He never had insurance block. He just went to work.

Well, he might have had insurance block if he’d tried to make selling insurance feel more like being a rodeo clown. I tell kids that the thing we call writer’s block happens when we try and make a story or a character fit into the hamster tunnel that we think they should take, instead of letting them run all over the place and explore the whole Habitrail set-up. Forcing the story rarely works, and it definitely robs you of the unexpected surprises that make writing actually fun. But you only get those surprises if you’re in the chair, because they only happen at a certain velocity.

I find that I get my best ideas in the shower. Standing up. Often while shampooing. Also, I have discovered that I experience that thing called “writer’s block” when I am bored. I am writing something and I have bored myself. Not a good place to be. So then I have to figure out why that happened and move the story in a different direction. Sometimes that direction is the garbage can, unfortunately. One sure-fire solution — my first step — is to eat ice cream. It always makes life better, don’t you agree? I see that you also teach workshops. Do you enjoy teaching writing? I don’t even like giving advice.

There are two things that I really do love about teaching: the first is that I almost always find that I know more than I think I do, and the second is that I always learn something new. I don’t go into a classroom thinking of myself as an expert—more like a hobbyist who’s been doing this for a while and has some stuff to say—and I’m always determined to keep my mind open to what the students have to say.

Oh, and there’s a third thing, which is that I sometimes get to teach with other writers who are really, really good at what they do. I’m slated to teach a class with Nicole Griffin at The Writing Barn in Austin next October, which I’m tremendously excited about. It’s called “Boys and Girls, Beasts and Ghouls,” and it’s all about how to create fully-realized, memorable characters.

Oh, and there’s a third thing, which is that I sometimes get to teach with other writers who are really, really good at what they do. I’m slated to teach a class with Nicole Griffin at The Writing Barn in Austin next October, which I’m tremendously excited about. It’s called “Boys and Girls, Beasts and Ghouls,” and it’s all about how to create fully-realized, memorable characters.

Teaching helps me avoid getting too deep into my own head while I’m writing, and to externalize/vocalize the process to keep the mental pipes from getting clogged. It’s invaluable to me.

Plus, I love a captive audience!

Thanks, Hannah. And good luck with your work.

–

Authors and illustrators previously interviewed here: Hudson Talbott, Hazel Mitchell, Susan Hood, Matthew McElligott, Jessica Olien, Nancy Castaldo, Aaron Becker, Matthew Cordell, Jeff Newman, Matt Phelan, Lizzy Rockwell, Jeff Mack, London Ladd, John Coy, Bruce Coville, Matt Faulkner, Susan Verde, Elizabeth Zunan, Robin Pulver, Susan Wood, and Florence Minor. To find past interviews, click on the “5 Questions” link on the right sidebar, under CATEGORIES. Or use the “Search” function.

Leave a Reply